-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Vendor-Managed Inventory for Automation: A Field Guide from the Systems Integrator’s Side of the Table

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why Inventory Is the Silent Constraint in Automation

On paper, automation projects live in drawings, I/O lists, and PLC programs. In the real world, they live or die on whether the right parts are physically in the plant when you need them. A single missing safety relay or network switch can stop a line, delay a startup, or push a shutdown window into overtime. I have seen more schedules blown by a backordered control component than by a late software change.

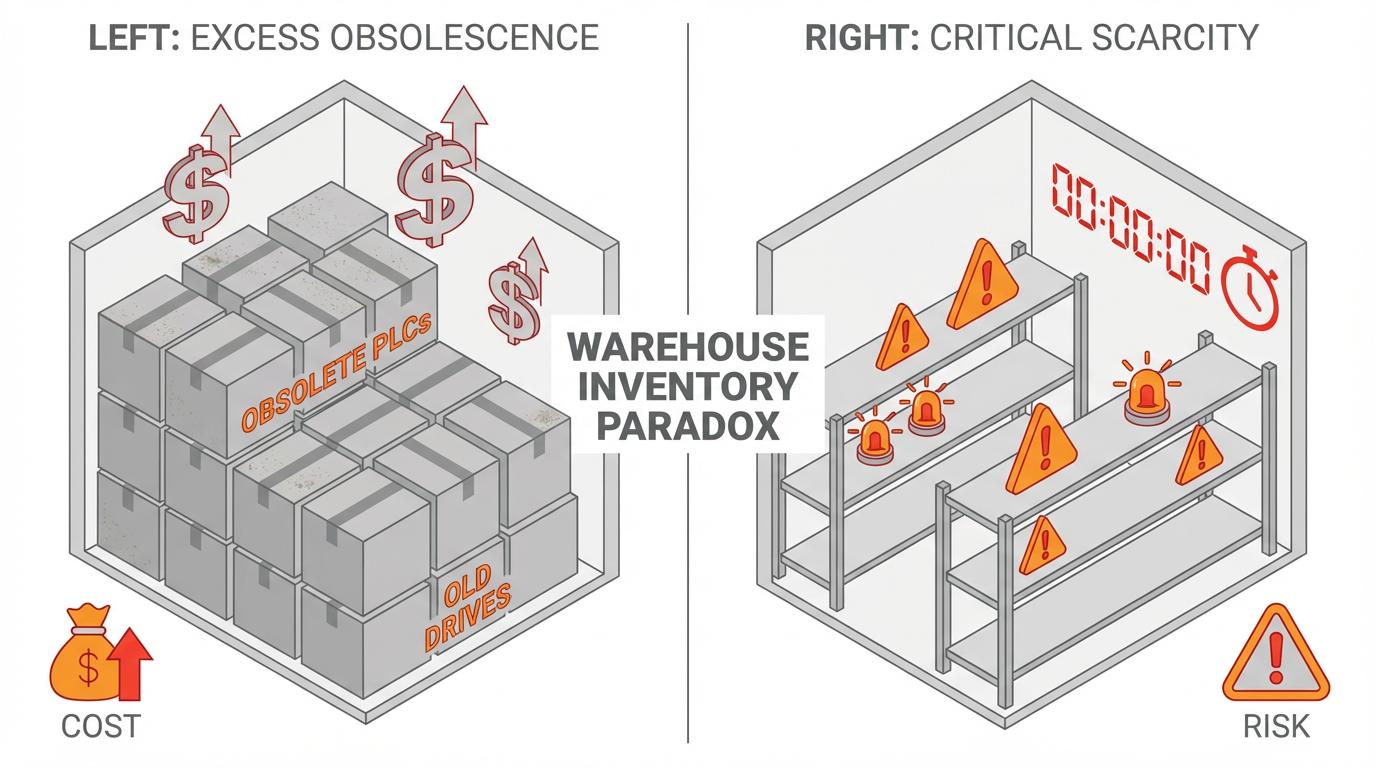

At the same time, most plants are sitting on shelves of slow‑moving spares: obsolete drives, old PLC cards, and boxes of specialty connectors for machines that were scrapped years ago. Industry research summarized by Deskera notes that manufacturing inventory carrying costs often land around 20–30% of the stock’s value per year once you roll up capital cost, storage, handling, insurance, and obsolescence. That matches what I see: the storeroom is a balance sheet problem as much as an uptime problem.

Vendor-managed inventory, or VMI, is one of the few strategies that actually improves both sides of that equation. Done correctly, it makes stockouts rarer, inventory turns faster, and plant personnel less distracted by counting bins and chasing orders. Done badly, it introduces new risks: over‑dependence on one supplier, bad data feeding bad replenishment decisions, and lack of visibility.

This article walks through VMI from the perspective of a veteran systems integrator who has watched it succeed in fastener rooms, MRO cribs, and automation spares cabinets across manufacturing, food processing, and industrial distribution. The focus is specifically on the automation and control hardware world: PLCs, drives, sensors, safety, panel hardware, and the thousands of C‑parts that keep controls running.

What Vendor-Managed Inventory Actually Is

Across sources such as SAP, Adobe, and Spendflo, the definition of vendor‑managed inventory is remarkably consistent: the supplier, not the customer, monitors inventory levels and takes responsibility for replenishment within agreed rules. Instead of your planners and buyers watching min/max levels and placing routine purchase orders, your supplier does that work based on shared data and a contract that defines service levels, ownership, and financial terms.

SAP describes VMI as a model where suppliers manage stock of their own products at the customer site using shared data and formal agreements. The supplier typically handles forecasting, replenishment, and restocking. Adobe emphasizes the collaboration aspect: VMI relies on near real‑time data sharing, clear agreements, and ongoing communication so the supplier can continuously adjust shipments based on demand trends and lead times. Spendflo points out that the key difference from traditional models and simple just‑in‑time arrangements is the shift of day‑to‑day replenishment responsibility to the vendor, driven by real usage data rather than your buyers’ manual ordering.

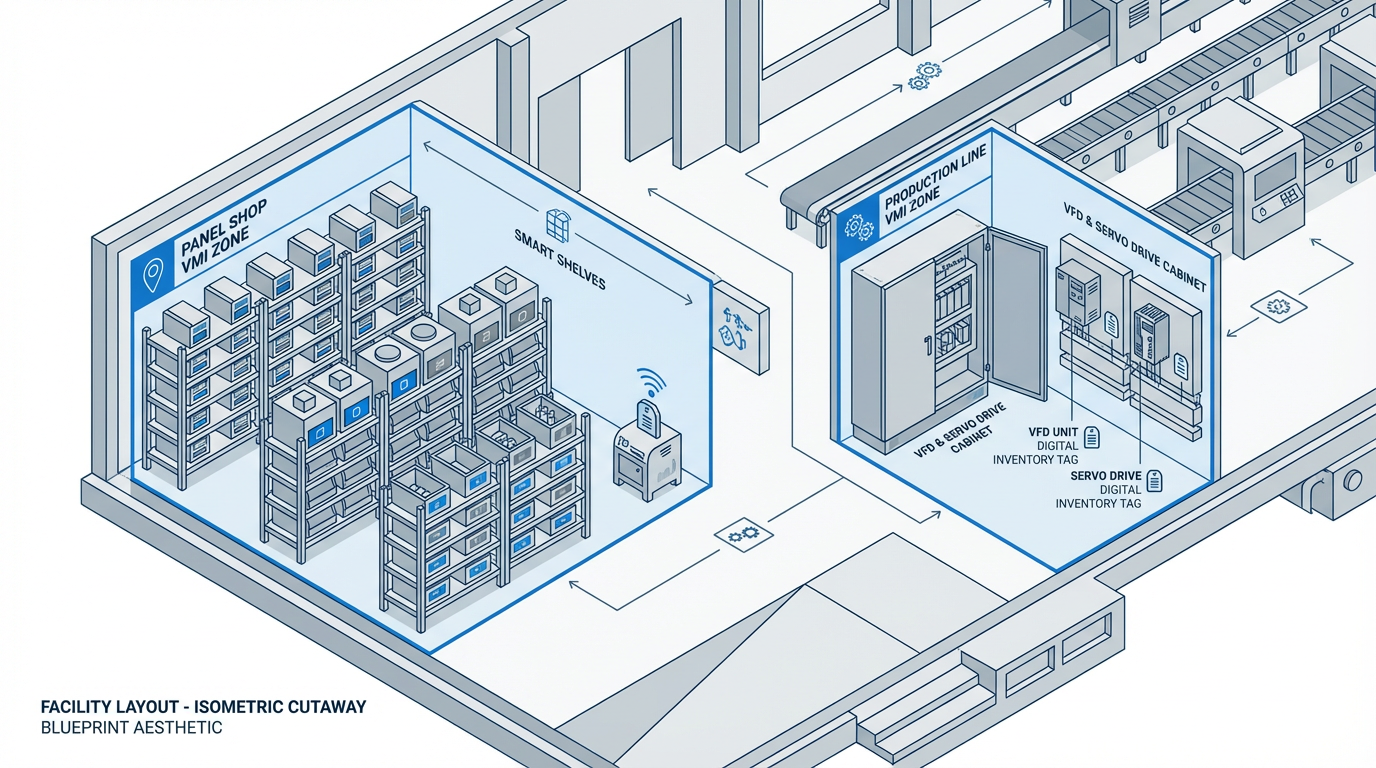

In automation, that might look like a controls distributor managing every fastener, terminal block, and standard sensor in your panel shop, or a drive supplier managing a consignment of critical VFDs and servo drives near your main production line.

Your team shares consumption and forecast data, and the supplier decides what to ship, in what quantity, and when, all within the limits you specify.

How VMI Works Day to Day in an Automation Environment

Under a typical VMI program, several building blocks come together.

First, there is structured data sharing. Adobe and SAP both stress that VMI thrives on abundant, timely data: on‑hand quantities, usage history, open orders, and sometimes even production schedules. In a plant, that data comes from bin counts, barcode scans, RFID reads, weight‑based bin scales, or integration with your ERP or maintenance system. The supplier sees the same or a filtered view of that data.

Second, the supplier uses that data for demand forecasting. Research from multiple sources, including TestEquity and university material on VMI software, highlights forecasting as the cornerstone. Algorithms look at historical usage, seasonality, promotions, and external factors like weather or shutdown schedules. They continuously compare forecasts to actual consumption and adjust. In an automation context, that may mean recognizing that certain sensor SKUs spike during an annual outage when a lot of equipment is rebuilt, or that fastener usage tracks with new machine projects rather than steady production volume.

Third, replenishment is automated within rules you agree up front. Minimum and maximum levels, target days of supply, lead times, safety stock, and packaging constraints all become parameters in the VMI system. When inventory falls below a calculated threshold, the system issues an order on behalf of your plant. Advanced VMI systems described by UMN and others add optimization algorithms that account for transportation cost, supplier production schedules, and service level targets.

Fourth, both parties measure performance. Common metrics cited by Adobe, SAP, Spendflo, and Nelson‑Jameson include fill rate or in‑stock performance, stockout frequency, inventory turnover, days of supply, on‑time‑in‑full delivery, and total carrying cost. In a well‑run VMI program, these metrics live in shared dashboards and are reviewed regularly between the plant and the vendor.

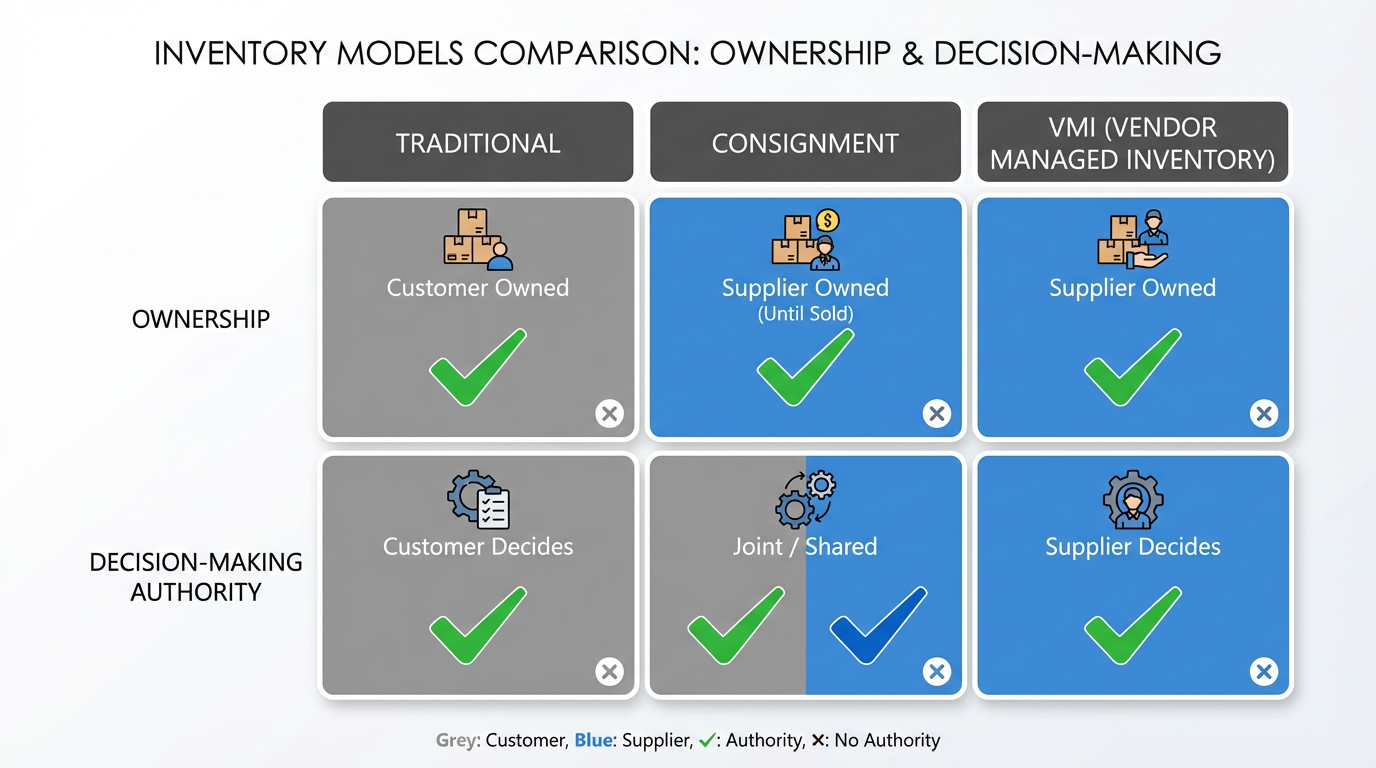

Finally, ownership and accounting are clearly defined. Some programs are traditional: you own inventory when it arrives, but the supplier manages its replenishment. Others are consignment, as described in multiple sources: the supplier retains ownership until you consume the material, which improves your cash flow but requires strong trust and accurate tracking. Hybrid models are common in automation: high‑value drives and PLCs on consignment, lower‑value C‑parts under traditional ownership but vendor‑managed.

The net effect on your day to day is simple: your storeroom or point‑of‑use cabinets are kept at agreed levels automatically, your plant staff spend far less time counting and ordering, and your supplier carries more of the analytical and operational load.

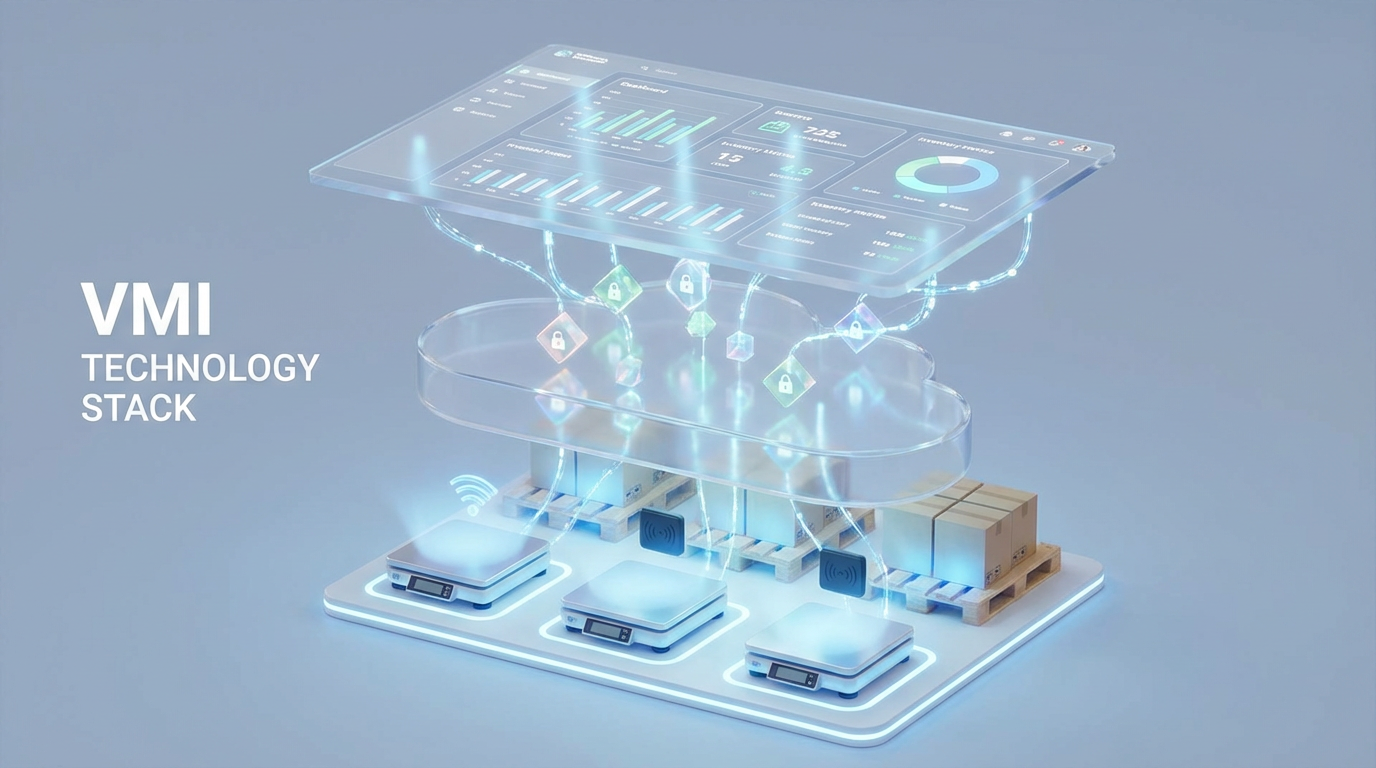

The Technical Backbone: From Bins and Scales to Cloud Dashboards

What makes modern VMI viable for automation is not just a contract but the technology that sits underneath.

Paragon Robotics describes weight‑based inventory systems that use load cell scales under bins to detect changes in stock level in real time. Each scale reports to a cloud platform that tracks inventory, generates automated orders, and provides dashboards and alerts accessible from any web‑enabled device. For small industrial parts and C‑parts, these systems avoid the need for manual counting or scanning altogether; every part removed from a bin is reflected as a change in weight.

ShelfAware outlines a different but complementary pattern: RFID tags attached to packages or even individual items. Their workflow is deliberately simple: technicians pick parts, swipe tagged items past a checkout station, and go back to work. Periodic audits with handheld RFID readers allow full‑room physical inventories in minutes instead of days, which is particularly attractive for storerooms with thousands of automation SKUs.

Field Fastener and ComponentSolutionsGroup emphasize yet another layer: cloud‑based portals and VMI software that integrate barcode scanning, bin‑level triggers, and multi‑site visibility. These platforms centralize inventory data across plants, support predictive analytics, and integrate with ERP and MRP systems through APIs or EDI.

The common thread across these technologies is real‑time or near real‑time visibility. UMN’s analysis of VMI software, along with SAP and Spendflo’s overviews, all highlight real‑time visibility as the linchpin of effective VMI. For automation, that means your supplier knows the moment a safety relay stock drops below a critical threshold at a remote plant, and can react before production notices.

The other critical thread is security. Providers such as SAP and Nelson‑Jameson point out that VMI requires sensitive operational and sometimes sales data to flow between companies. Best practice is to use secure, purpose‑built platforms with encryption, strong access control, role‑based permissions, and regular security audits. For plants in regulated sectors like food or medical, Paragon Robotics notes that compliance with relevant federal security standards is essential.

How VMI Compares to Other Inventory Models

For many engineering managers, the natural question is how VMI differs from traditional inventory management or simple consignment. A concise way to contrast them is in terms of who owns stock and who actually makes replenishment decisions.

| Model | Who owns the stock on site | Who decides what to replenish and when | Typical use in automation and controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional buyer‑managed | Customer owns upon receipt | Customer planners and buyers | General MRO, ad‑hoc spares, low‑volume or specialty items |

| Consignment | Supplier owns until consumption | Customer orders or withdraws; supplier just invoices | High‑value drives or PLCs where cash flow is a concern |

| Vendor‑managed inventory | Ownership varies; traditional or consignment | Supplier plans, forecasts, and triggers replenishment | C‑parts, panel hardware, fasteners, standard sensors and safety devices |

SAP differentiates VMI from both simple consignment and basic just‑in‑time. In just‑in‑time, responsibility for planning and ordering stays with the buyer; in consignment, ownership shifts but not the planning function. VMI combines the two: suppliers may own the stock and always take on active, continuous management of inventory levels.

For a controls department, the key advantage is that your engineers and maintenance planners do not have to be amateur inventory analysts.

The trade‑off is that you have to define your guardrails and governance very clearly so you do not surrender strategic control.

Why Automation and Control Hardware Are Prime Candidates for VMI

Many of the industries highlighted by SAP, Gexpro Services, and others—automotive, aerospace, healthcare, and electronics manufacturing—are heavy users of automation. The underlying reasons they lean into VMI apply directly to control hardware and related components.

First, automation environments have a long tail of C‑parts. ComponentSolutionsGroup notes that C‑parts are low‑cost, high‑variety, production‑critical items such as fasteners, washers, and rivets. In automation, you can add terminal blocks, DIN rail, cord grips, wire ferrules, fuses, enclosure hardware, and standard proximity sensors. These parts are tailor‑made for VMI because the cost of a stockout is measured in downtime, while the cost of overstock is hidden but real.

Second, many plants operate across multiple buildings or sites. Inovar Packaging describes using VMI with distributed warehouses to ship directly to multiple production sites, eliminating internal transfers. Automation spares behave the same way: you want the right PLC card or VFD in the right plant without turning your maintenance team into a logistics company.

Third, automation gear changes fast. Product life cycles on drives, PLC platforms, and network devices are shorter than the life of the machines they control. VMI providers who live in these catalogs often have better visibility into upcoming obsolescence and replacement paths than the average plant. TestEquity and SAP both point out that suppliers in VMI programs bring product expertise, compatibility guidance, and trend insight that go beyond simple order fulfillment.

Finally, automation is often the bottleneck for production. OEM Materials highlights a case where a VMI program for an automotive manufacturer reduced stockouts by 20% and carrying costs by 15%, with measurable improvements in on‑time delivery. ComponentSolutionsGroup reports that 78% of manufacturers using VMI see improved inventory turnover, procurement lead times drop by about 20%, and overall inventory costs fall by roughly 10–15%. Those numbers come from broader C‑part programs, but the same dynamics apply when a single missing sensor or fastener can delay a machine start or a line restart.

Benefits You Can Realistically Expect

Across sources like Adobe, SAP, Gexpro Services, NetSuite, and several industry case studies, the benefits of VMI cluster in a few practical buckets.

Availability improves. Stockouts become rarer because the supplier is watching inventory continuously instead of your team spot‑checking bins. BCEPI and Nelson‑Jameson both emphasize that VMI reduces the risk of both stockouts and overstocks by placing the responsibility for monitoring and replenishment with a party that is focused on it full‑time.

Inventory turns increase and carrying costs drop. ComponentSolutionsGroup’s figures on improved turnover and 10–15% inventory cost reduction are consistent with what NetSuite and Deskera describe as the impact of modern inventory strategies. When you carry fewer months of supply on the shelf and clear obsolete items faster, you reduce the amount of cash tied up in stock, which matters even more when that stock is high‑value automation hardware.

Administrative workload decreases. Multiple sources, including Gexpro Services, Spendflo, and Field Fastener, note that VMI reduces the day‑to‑day work of counting, ordering, and expediting. In a controls department, that translates to technicians spending more time troubleshooting and less time in the storeroom, and buyers spending more time on strategic sourcing and less on routine purchase orders.

Forecasting and planning get better. Vendor‑side analytics tools, as described by UMN, SAP, and Gartner’s coverage of VMI platforms, use historical data and advanced forecasting to smooth demand. Suppliers with many customers in similar industries can detect patterns your plant might not see, such as common seasonality or the impact of large scheduled shutdowns.

Collaboration strengthens. Gexpro Services, Nelson‑Jameson, OEM Materials, and SAP all describe VMI as a partnership not a transaction. With shared data and shared KPIs, supplier and customer sit on the same side of the table more often, which tends to make problem‑solving faster and relationships more resilient during disruptions.

Financially, even modest improvements matter. If your plant’s carrying cost is in that typical 20–30% range and VMI helps you reduce average inventory by just a fraction, the savings compound year after year. The case data from OEM Materials and ComponentSolutionsGroup shows that double‑digit percentage reductions in specific cost buckets are achievable when programs are well designed.

Risks and Failure Modes You Need to Plan For

The upside of VMI is substantial, but the risks are real if you treat it as an autopilot switch instead of a redesigned process.

Loss of perceived control is the first concern most engineering managers raise. SAP, Spendflo, and Nelson‑Jameson all list dependency on suppliers and reduced day‑to‑day control as core risks. The answer is not to avoid VMI but to design it with clear boundaries: which SKUs are in scope, what min/max limits are acceptable, what approval thresholds exist for changes to stocking strategy, and how you can exit a program if performance slips.

Data quality is the second major risk. Adobe, SAP, and UMN all warn that messy or delayed data will drive bad replenishment decisions. If technicians forget to scan items, bins are mislabeled, or integrations are unreliable, the VMI engine is operating blind. Before you scale VMI, you need stable processes and technology for accurate data capture, whether that is RFID, barcodes, scales, or carefully designed manual workflows.

Security and privacy cannot be an afterthought. Adobe and SAP highlight the sensitivity of the data shared: consumption by line, plant, and sometimes customer. Nelson‑Jameson recommends encryption, strong access control, confidentiality clauses, and regular security audits. For plants that must comply with regulatory or customer security requirements, you should treat VMI platforms like any other critical application in your cybersecurity program.

Forecasting errors and demand volatility are a third risk area. Even the best algorithms struggle with events like a sudden product change, a recall, or a new customer win. Spendflo and Nelson‑Jameson both stress the need for flexible, scenario‑based planning and quick communication when demand patterns change. In automation, that might mean planning ahead for a major modernization project so the VMI program does not misinterpret a temporary project spike as a new baseline.

Vendor capability is the last big risk. Several sources, including Adobe, Nelson‑Jameson, and SAP, warn that not all suppliers have the data skills, analytics platforms, or operational discipline to run VMI well. A vendor who is excellent at selling hardware is not automatically excellent at managing your inventory.

The mitigation is disciplined vendor selection, clear contracts and SLAs, and pilot programs before wide rollout.

Gartner’s coverage of VMI tools suggests comparing vendors on forecasting capability, data integration, collaboration features, and cross‑functional workflows, not just on price.

Designing a VMI Program for Automation and Control Hardware

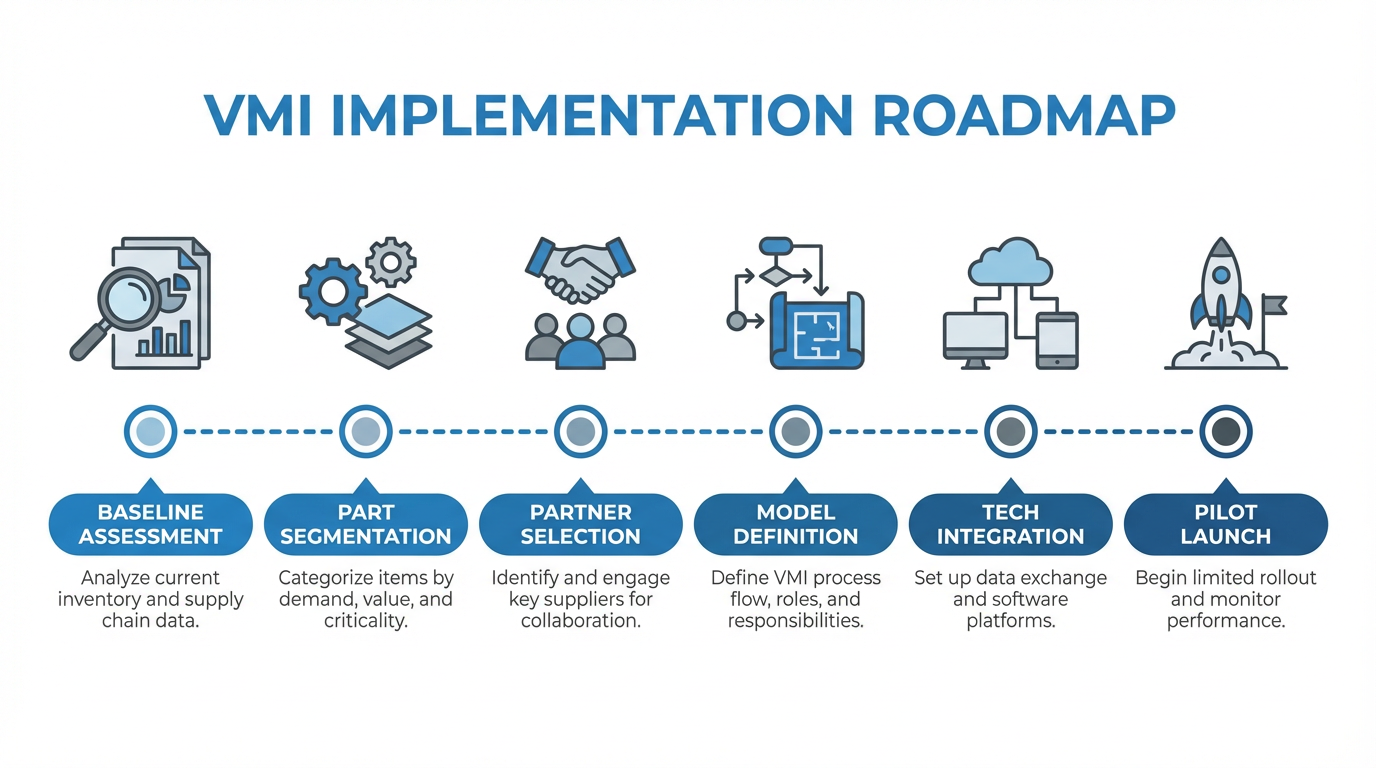

In practice, a good VMI program looks far more like a joint engineering project than a purchasing tactic. Based on patterns described by AFC, Nelson‑Jameson, OEM Materials, and others, along with what I have seen on plant floors, a pragmatic path usually follows several stages.

The practical starting point is to baseline your current state. That means mapping your existing inventory processes, identifying chronic stockouts and overstocked items, and quantifying carrying costs where possible. Verified Market Reports projects roughly 10% annual growth in VMI systems between 2025 and 2033, but that momentum only matters if you understand your own baseline so you can measure improvement.

Next, segment your parts. NetSuite recommends ABC analysis and similar segmentation methods, and ComponentSolutionsGroup applies these effectively to C‑parts. In automation, I usually see three buckets emerge: critical production spares such as PLC processors, drives, and safety controllers; medium‑critical items such as standard I/O cards and network hardware; and high‑volume C‑parts like fasteners, terminal blocks, and common sensors. VMI almost always starts with the third bucket and sometimes parts of the second.

Once you have a candidate scope, select potential partners. SAP, Adobe, and Spendflo all advise choosing vendors with a track record in VMI, strong data and analytics capabilities, and experience in your industry. For automation, that often means either a controls distributor with a mature VMI platform, a fastener or C‑part specialist with IoT‑enabled systems, or a hybrid that can handle both hardware and commoditized items. AFC’s program structure and OEM Materials’ JIT‑oriented VMI demonstrate the value of partners who know manufacturing operations, not just inventory theory.

Then define the commercial and operational model. Will high‑value automation parts be on consignment, with the supplier retaining ownership until you use them, while low‑value items are traditional ownership but vendor‑managed? What are the fill rate targets for critical SKUs, what is the acceptable window for stockouts if they happen, and how will you handle obsolete items? Nelson‑Jameson and SAP both stress clearly defined roles, KPIs, and contracts that cover ownership, liability, payment timing, and return policies.

Integration and technology come next. UMN, Paragon Robotics, ShelfAware, and Deskera all highlight the importance of integrated systems: VMI platforms must exchange data with your ERP, CMMS, or MES, and field technologies such as scales, RFID stations, or scanners must fit your plant’s reality. For example, ShelfAware deliberately designs fast, low‑friction workflows to replace manual audits that used to take days or weeks; any solution you select should respect your operators’ time the same way.

Finally, run a pilot and treat it as a learning exercise. Nelson‑Jameson and ComponentSolutionsGroup both recommend starting with a subset of items or a limited area, then refining parameters, correcting data issues, and validating KPIs before scaling. AFC formalizes this through phases of discovery, program development, installation, training, and regular reviews; that structure translates well into automation projects too.

What Good Looks Like: KPIs and Governance

The difference between a VMI program that quietly adds value for years and one that ends in frustration is governance. Several sources, including Adobe, SAP, Spendflo, and Nelson‑Jameson, converge on a common set of metrics and practices.

Operationally, you should track fill rate, stockout frequency, and days of supply for in‑scope items. Inventory turnover and carrying cost provide financial signals. On‑time‑in‑full delivery is useful where replenishment is handled through shipments rather than on‑site vendor visits. Forecast accuracy helps both parties understand how well the system anticipates demand.

Process‑wise, regular joint reviews are essential. AFC describes strategic business reviews between customer and vendor teams to monitor performance and drive continuous improvement. In my experience, a quarterly review cadence works well for most plants, with monthly exception reviews during the first year of a new program.

Training and change management should not be overlooked. SAP cites research that up to 70% of digital transformation projects fail mainly due to poor planning, siloed cultures, and inadequate training. VMI sits at the intersection of supply chain, maintenance, and engineering, which makes it vulnerable to those pitfalls. Clear communication of roles, simple front‑line workflows, and visible leadership support go a long way.

When VMI Is Not a Good Fit

Despite the benefits, there are situations where VMI is either a poor fit or should be applied very selectively.

Spendflo notes that VMI is best suited to relatively steady demand and long‑term vendor partnerships. If your automation demand is dominated by irregular projects, one‑off retrofits, or highly customized machines, then a traditional project‑by‑project approach may make more sense, with VMI reserved for standard components and MRO items.

SAP and Nelson‑Jameson both highlight environments with weak data quality, fragmented systems, or strong resistance to data sharing as problematic. Without good, shared data, VMI reverts to guesswork. If your organization is not ready to expose usage and stock levels to a supplier, or if your systems cannot reliably produce that data, you should fix those issues first.

Finally, if your preferred suppliers lack VMI experience, robust technology, or analytical capability, it is better to wait than to roll out a program that will fail. ComponentSolutionsGroup and OEM Materials both show what good looks like in terms of metrics and results; if a potential partner cannot explain their platform, KPIs, and case history in similar terms, that is a warning sign.

Short FAQ for Automation Leaders

Question: Does VMI mean I lose control over my spares room? Not if it is designed well. You still define which items are in scope, what service levels you expect, how much inventory you are comfortable carrying, and which items must always be approved before changes. The supplier executes within those guardrails and reports performance against agreed KPIs. Think of it as outsourcing execution, not strategy.

Question: Can VMI work when I buy from multiple automation vendors? Yes, but it requires clarity. Some plants use VMI with a fastener or C‑part specialist plus a separate program with a controls distributor. ShelfAware’s “Cloud Sourcing” concept even envisions multiple independent suppliers sharing a common digital platform for one large manufacturer. The key is to ensure that item ownership, data flows, and responsibilities are clearly divided and that each supplier’s VMI scope is well defined.

Question: How long does it take to implement a VMI program? BCEPI notes that implementations typically take around three months or longer, depending on complexity, data integration, company size, and training needs. That aligns with what I see in automation: a focused pilot on C‑parts can go live in a few months, while multi‑site programs with ERP integration and consignment models may take longer. The critical factor is to treat it as a structured project with milestones rather than an informal experiment.

Closing Thoughts from the Systems Integrator’s Side

Over the years I have watched plants invest heavily in new control platforms, only to continue managing critical spares with clipboards and guesswork. Vendor‑managed inventory is not glamorous, but when it is well designed and grounded in solid data, it quietly removes one of the biggest sources of risk and waste in automation projects. If you approach VMI as a structured partnership, backed by the right technology and clear governance, it becomes exactly what a good control system should be: predictable, transparent, and reliable enough that you stop thinking about it and focus on running the plant.

References

- https://ddg.wcroc.umn.edu/vendor-managed-inventory-software/

- https://www.fieldfastener.com/data-driven-vmi

- https://www.afcind.com/afc-news/what-is-vendor-managed-inventory-vmi-and-how-does-it-work

- https://www.authentise.com/post/vendor-managed-inventory-impact-manufacturing

- https://www.bcepi.com/fasteners-101/does-vendor-managed-inventory-improve-the-supply-chain

- https://www.extensiv.com/blog/vendor-managed-inventory

- https://www.fishbowlinventory.com/blog/vendor-managed-inventory

- https://inovarpackaging.com/optimizing-your-supply-chain-with-vendor-managed-inventory-and-eoq-strategies/

- https://ww2.nelsonjameson.com/blog/vendor-managed-inventory-optimize-food-processing-supply-chains

- https://www.oemmaterials.com/post/vmi-enables-jit-success

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment