-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Extended Warranty Options for Industrial Components: A Systems Integrator’s View

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why Warranties Matter More Than Ever in Industrial Automation

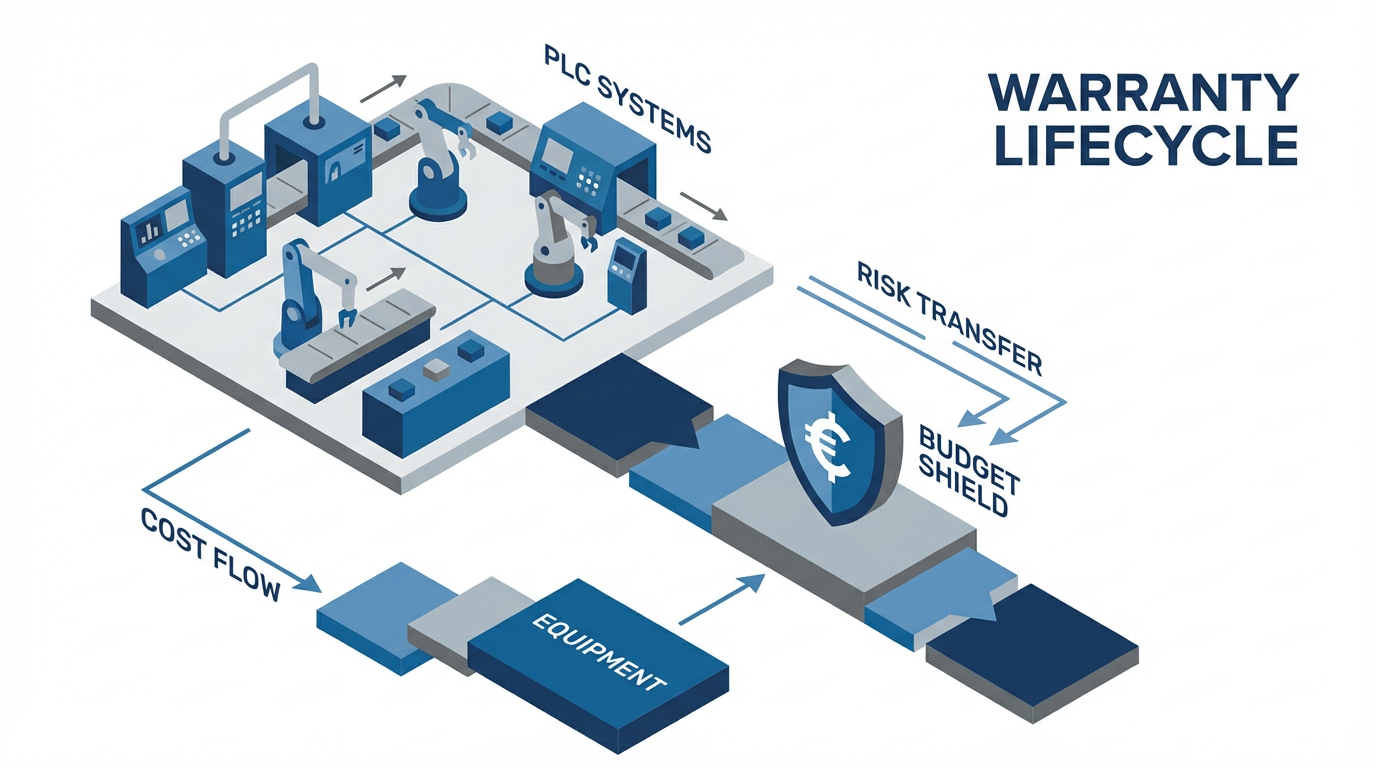

When you run a plant around programmable logic controllers, drives, robots, motion controllers, and safety systems, the warranty is not just a legal document in a folder. It is part of your risk-control strategy.

In automation, a warranty is the supplier’s written promise that the equipment will perform as expected for a defined period and that defects caused by manufacturing or design will be repaired or replaced at the supplier’s cost. That definition comes through clearly in industrial automation guidance from sources such as Qviro. In practice, it means that when a new servo drive dies from a factory defect, the supplier absorbs the parts and sometimes the labor, not your maintenance budget.

The stakes are high. An unexpected failure in a robot cell or a main PLC rack can idle a production line and ripple into missed shipments and penalty clauses. Articles on equipment protection plans from Liberty Insurance emphasize that equipment failures drive costly downtime and unpredictable repair bills, and they point out that many high‑value machines in North America are now sold with some form of extended protection plan precisely because the financial impact of failure is so severe.

As a systems integrator and project partner, I have seen both ends of the spectrum. Plants that treat warranties as an afterthought often discover that their “coverage” does not help when a critical component fails in a harsh application or at high hours. Plants that treat warranties as part of total cost of ownership, on the other hand, tend to have fewer budget shocks and a clearer playbook when something breaks.

Extended warranty options for industrial components sit in the middle of this picture. Done well, they convert unpredictable repair risk into a known cost and support uptime. Done poorly, they simply transfer money from your budget to a provider with little practical benefit. The rest of this article is about telling those two apart.

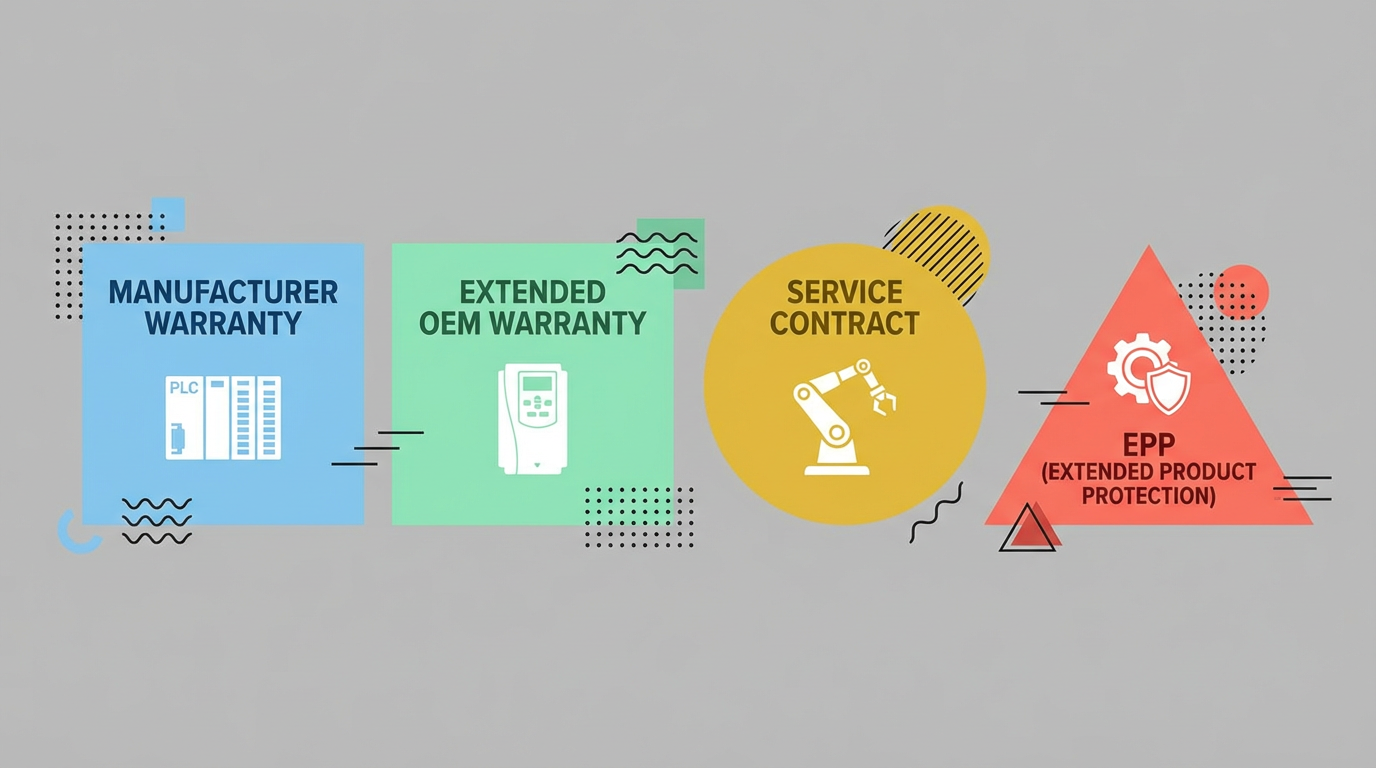

Core Definitions: Warranty, Extended Warranty, Service Contract, and EPP

Before choosing coverage, it helps to use the terms precisely. The research on warranties across industries uses a common set of definitions that apply neatly to industrial components.

A manufacturer warranty is included in the purchase price. As Safeware and Qviro both outline, it is a guarantee from the product’s producer that the item will meet stated quality and performance standards for a set period. It primarily covers defects in materials and workmanship, not damage from accidents, misuse, or normal wear and tear.

An extended warranty, in the industrial context, is additional coverage beyond that standard manufacturer warranty. Equipment-focused sources such as Equipment Dealer Magazine and ProtectMyIron highlight that extended warranties typically focus on high‑cost assemblies such as engines, powertrains, hydraulics, and complex electronics. For automation components, the analog is added coverage on controllers, drives, robots, and key electronics after the standard one‑year period, often for specific time and usage limits.

A service contract or extended service contract is a paid agreement that looks like an extended warranty but is technically distinct. Equipment Dealer Magazine describes Extended Service Contracts (ESCs) as protection plans that usually begin after OEM warranty ends, administered by insurance or finance companies rather than the OEM warranty department. They function similarly to insurance: you pay to shield your organization from large, unexpected repair costs and from inflation in parts and labor.

An equipment protection plan, or EPP, is a broader form of extended service contract. Liberty Insurance defines EPPs as extended service agreements that kick in after the manufacturer’s warranty, covering mechanical and electrical failures and often normal wear and tear, power surges, and operational breakdowns. They emphasize that EPPs are not the same as property insurance; they cover internal breakdowns, while insurance covers external perils such as theft, fire, and floods.

In industrial automation, you will see all four labels used.

The critical point is not the label but the answers to a few questions: when does coverage start and end, which components and failure modes are included, who performs the work, and how claims really play out.

The table below summarizes the main categories from an industrial components perspective.

| Term | Typical payer and start point | What it usually covers for industrial components |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer warranty | Included in purchase; starts at delivery or installation | Defects in materials and workmanship on PLCs, drives, robots, sensors, HMIs |

| Extended OEM warranty | Paid add‑on; overlaps or follows base period | Added years or operating hours on major components; often parts and sometimes labor |

| Extended service contract | Paid plan, often via third party; starts after OEM coverage | Mechanical and electrical failures, sometimes wear items, with more fine print |

| Equipment protection plan | Extended service contract variant emphasizing internal failures | Broader breakdown coverage and sometimes wear and tear, beyond defect-only terms |

What Standard Warranties Actually Cover on Automation Hardware

Typical Coverage

For most industrial automation vendors, the standard warranty is short and focused. Qviro notes that in industrial automation, warranty coverage usually includes factory defects, internal component failures, and software bugs that surface in normal use within the coverage period. Equify Financial’s discussion of heavy equipment warranties aligns with this, indicating that basic warranties generally last about 12 months after delivery.

Applied to automation, that often means one year of coverage on items such as PLC CPUs, I/O cards, drives, and robots, measured from delivery or installation. Some suppliers mirror the pattern mentioned by Safeware for consumer equipment and by Gregory Poole for Caterpillar equipment: they assign different warranty periods to specific critical components. For example, a robot might have one term for the controller and another for the mechanical arm, or a drive might have separate coverage on the power section and the control electronics.

Within that window, if a covered component fails due to a defect, the manufacturer typically repairs or replaces it at no cost for the part itself, and sometimes covers labor and shipping. Gregory Poole’s summary of Caterpillar warranties illustrates the pattern: standard limited warranties cover parts and labor for defined periods or hours on new equipment and parts. Automation vendors frequently follow an analogous approach.

Common Exclusions and Misconceptions

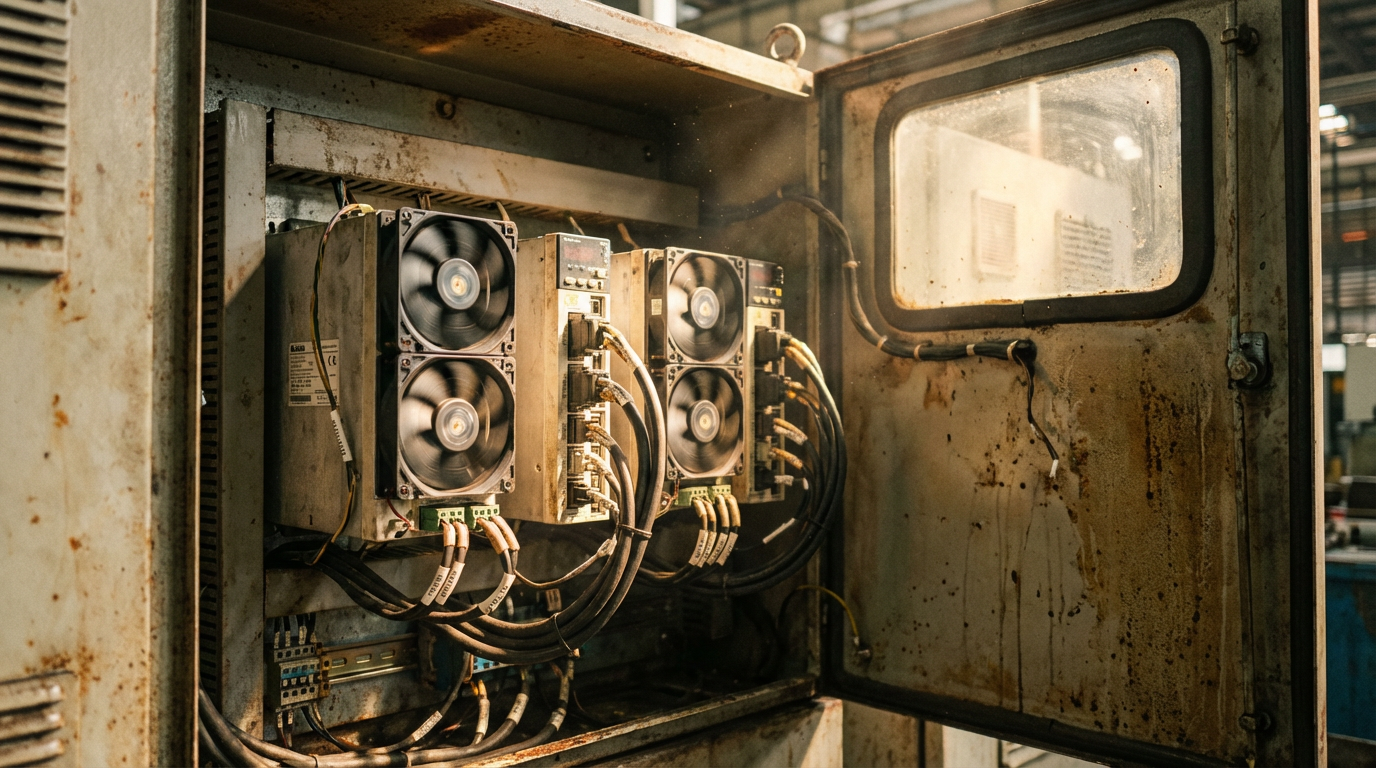

The exclusions matter just as much as the inclusions. Across sources such as Safeware, Qviro, Liberty Insurance, and several heavy equipment warranty guides, the same exclusions show up repeatedly.

Normal wear and tear is usually not covered under a basic manufacturer warranty. Safeware gives simple consumer examples and notes that gradual deterioration from regular use is excluded. For industrial components, that maps to encoder wear, fan failures after long use, worn relays, or connector fatigue that develop over years rather than from a manufacturing defect.

Accidental damage, misuse, or neglect is another major exclusion. Qviro notes that damage from incorrect use, incompatible materials, poor installation, skipped maintenance, or unapproved modifications typically falls outside standard warranty coverage. In an automation setting, that includes wiring a drive incorrectly, running a servo beyond specified load or temperature, or ignoring required filter changes.

Unauthorized repairs can void coverage. Safeware points out that unauthorized repairs or modifications by non‑approved service providers may void the warranty, because the manufacturer can no longer vouch for the product’s condition. Qviro repeats this warning: unapproved modifications are a common way to lose protection. If you routinely rework boards, swap parts between units, or apply firmware patches from unofficial channels, do not assume the OEM will honor the warranty when something fails.

A final misconception is that “everything” is covered for the entire lifespan of the machine. Qviro notes that warranty terms are time‑limited, commonly about 12 months for industrial automation hardware, with paid extensions available. Consumer Reports adds that beyond written warranties, there are implied warranty concepts in general consumer law, but these are complicated and heavily jurisdiction‑dependent. In industrial B2B contexts, you should not plan your risk strategy around implied warranties.

Conditions That Can Void Coverage

Heavy equipment warranty guides from Construction Equipment, Equipment Dealer Magazine, and Gregory Poole emphasize that warranty validity depends on using equipment in approved applications and conditions, professional installation, and adherence to specified maintenance procedures. The same logic applies to automation hardware.

If you install a drive in an enclosure that exceeds the specified ambient temperature, operate a robot in a washdown environment with a non‑washdown rating, or run a PLC power supply at constant overload, you are giving the supplier grounds to deny claims. During dispute discussions, suppliers often request installation records, environmental data, and usage logs, which is why the parts warranty sections in those guides stress documentation and compliance.

For integrators and end users, this means that engineering decisions about enclosures, cooling, derating, and jobsite conditions are not just technical issues; they are warranty issues.

Extended Warranty Options for Industrial Components

Extended OEM Warranties on Automation Hardware

Many automation vendors offer extended OEM warranties that continue coverage beyond the base period. The structure resembles what Equify Financial and Carter Machinery describe for heavy equipment: a basic warranty included with purchase and optional extended coverage for an additional fee, with stricter terms and conditions and maximum limits in time and usage.

On automation components, an extended OEM warranty typically adds a defined number of years on major items such as controllers, drives, and robots. Coverage may be full (parts and labor) or limited (parts only), and sometimes it only covers specific systems, for example, drive power sections or robot gearboxes. Articles from ProtectMyIron and Construction Business Owner show how construction equipment warranties can be configured as engine‑only, powertrain‑only, or powertrain plus hydraulics; automation OEMs follow a similar pattern with control and motion systems.

Extended OEM warranties are usually priced based on component cost, complexity, and expected failure rates.

Qviro notes that extended warranties on industrial automation systems can cost anywhere from a few hundred to several thousand dollars depending on the system, which lines up with vehicle warranty pricing discussed by Endurance Warranty. For a mid‑range PLC or drive system, the extended warranty cost is often small compared to the total project value, but not trivial compared to the replacement cost of a single module.

Third‑Party Extended Warranties and Equipment Protection Plans

Beyond OEM programs, third‑party providers offer extended warranties and equipment protection plans for industrial, construction, and mixed fleets. Liberty Insurance describes equipment protection plans that add two to five years of protection beyond the standard warranty and often cover normal wear and tear, power surges, and operational breakdowns. GT Mid Atlantic, partnering with an insurance administrator, illustrates the model in heavy equipment: extended warranties that cover unexpected repair costs, increase resale value, and can be financed via installment contracts or leases.

Industrial plants that run a mix of automation and mobile equipment sometimes use the same third‑party for both, particularly for large multi‑site portfolios. The advantages are the broader scope and potential inclusion of wear, travel costs, and even rental equipment support, as Liberty Insurance and Gregory Poole both highlight for equipment protection plans.

The main caution is that, as Consumer Reports and Qviro both stress in their domains, these plans often have extensive fine‑print exclusions. Automotive service plans sold by third‑party companies, in particular, have generated many complaints about claims being refused on the basis of narrow coverage definitions. For industrial components, that translates to carefully scrutinizing exclusions around surge events, environmental conditions, firmware modifications, and integration with non‑OEM hardware.

Extended Service Contracts and ESCs

Equipment Dealer Magazine draws a useful distinction between OEM extended warranties and Extended Service Contracts or ESCs. ESCs typically begin after all OEM warranty expires, are administered by insurance or finance companies, and are designed to function like long‑term repair‑cost protection in the face of rising parts prices. They give an example where a replacement engine’s list price increased more than 20 percent over five years, illustrating why locking in coverage matters.

For industrial components, ESCs can be used to extend protection over a multi‑year lifecycle when you intend to keep assets long after the base automation hardware is out of production. They are particularly relevant when your line uses proprietary automation technology that is costly or slow to replace and where component inflation and obsolescence can create severe budget and uptime shocks.

In practical terms, an ESC on automation hardware might combine parts and labor coverage on drives, PLCs, robots, and key sensors beyond the OEM window, often with deductibles and clearly defined service networks. Operationally, they are usually purchased through a dealer or integrator, with the dealer filing claims and receiving reimbursement, similar to the process Equipment Dealer Magazine describes in heavy equipment.

Pros and Cons of Extended Warranties for Industrial Components

From a plant’s perspective, extended warranties are a trade: a known, upfront cost in exchange for reduced uncertainty and potentially higher uptime. The research and field experience show a mix of genuine benefits and common pitfalls.

On the benefits side, the main value is risk transfer. Extended warranty discussions in Equipment World and ProtectMyIron frame them as a way to turn large, unpredictable repair bills into stable budget items. For industrial components, that means a fixed cost in your capital or maintenance budget instead of wondering which drive or robot will fail at the worst possible time and how much it will cost.

Extended warranties also support cash‑flow control and planning. Liberty Insurance and ProtectMyIron both emphasize that premiums create predictable, stable costs that hedge against inflation in parts and labor and help avoid surprise expenditures that derail business plans. Equipment Dealer Magazine’s engine price example underscores that repair costs can rise dramatically over a few years; locking in coverage can insulate you from those increases.

Uptime and service quality can improve as well. Gregory Poole points out that strong warranties and protection plans often include prompt dealer servicing, rental machines, and coverage for transport and travel costs, all of which minimize downtime. In automation, extended warranties that include priority support, remote diagnostics, and guaranteed response times can materially cut the length and impact of failures.

Resale value is another advantage. Boom & Bucket reports that heavy equipment with warranties can sell for around 15 percent more than comparable units without coverage, especially in the used market. GT Mid Atlantic and Carter Machinery note that transferability of extended coverage improves marketability. For industrial assets, the same principle applies: a production line or robot cell with transferable, documented coverage is more attractive on the secondary market than one with no support.

On the downside, extended warranties are not automatically good value. Consumer Reports’ analysis of extended consumer warranties shows that service plans often fail to deliver clear cost savings, with customer satisfaction levels similar whether repairs were paid out of pocket or via extended plans. They highlight common issues such as long repair times and multiple attempts to fix the same problem under extended coverage. While that research focuses on appliances, the underlying lesson carries into industrial domains: paying for an extended warranty does not guarantee better outcomes unless the provider and terms are strong.

Fine‑print exclusions and claim denials are another risk. Qviro and Liberty Insurance list extensive exclusions for misuse, improper maintenance, cosmetic damage, consumables, and unauthorized repairs. Consumer Reports notes that third‑party auto service plans often refuse claims by saying the problem is not covered. Industrial plans can be similar: if you do not adhere strictly to maintenance schedules, documentation requirements, and operating conditions, you may find that a “covered” failure is ruled out of scope.

Cost is the final major drawback. Qviro and Endurance Warranty both describe extended warranties that can cost from a few hundred to several thousand dollars. If your components are relatively inexpensive or lightly used, or if your plant has strong maintenance and spare‑parts strategies, self‑insuring may be more economical. My‑Equipment’s discussion of going warranty‑free for fleets with robust internal capabilities underscores that warranties should be evaluated against your actual risk appetite, not bought by default.

In short, extended warranties for industrial components are neither magic shields nor automatic waste.

They are financial instruments that can be highly effective when matched to the right assets, risks, and providers, and poor investments when bought on autopilot.

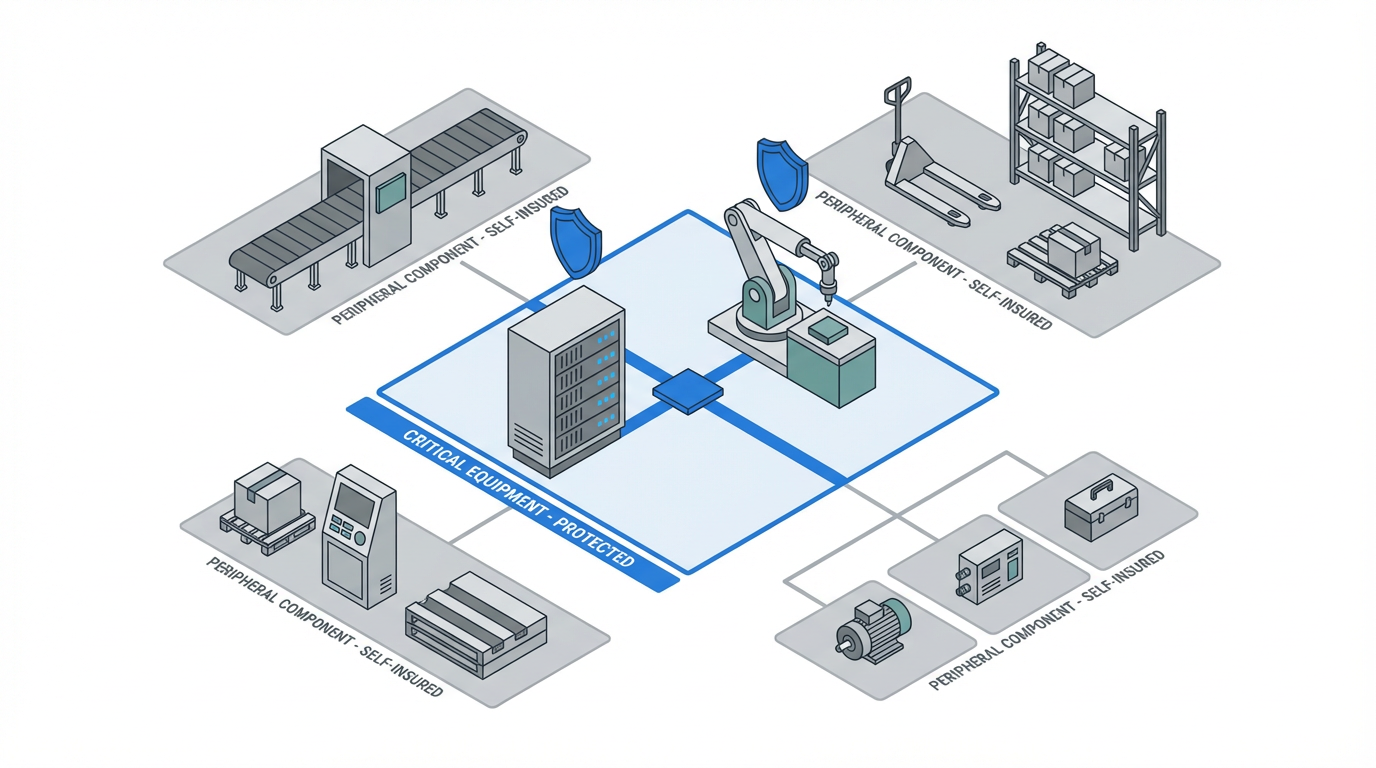

When Extended Warranties Make Sense in a Plant Environment

Across the industrial and heavy‑equipment sources, a pattern emerges around when extended warranties tend to deliver value.

They are most compelling on high‑value, mission‑critical components. Qviro specifically highlights high‑value, intensively used, or process‑critical automation systems as strong candidates for extended coverage, while noting that occasional‑use research systems may not justify the cost. Equipment World makes the same point for machines with high hours, harsh applications, remote locations, or long planned ownership periods. Applied to automation, this includes main PLC racks, central drives, and robot controllers that can stop entire lines if they fail.

Extended warranties also make sense when your cash reserves or in‑house maintenance capabilities are limited. Equipment World notes that contractors without strong internal shops benefit more from extended coverage. Plants with small maintenance teams, limited spare‑parts budgets, or remote locations where response logistics are difficult can use extended coverage and associated support models to compensate for these constraints.

The case is weaker for low‑criticality or lightly used assets. Qviro points out that for occasional‑use research systems, downtime is less costly, and extended warranties may be unnecessary. My‑Equipment suggests that firms with mainly vintage equipment and strong internal maintenance and record‑keeping can deliberately choose a warranty‑free or limited‑warranty strategy if their risk appetite and financial strength allow. For many smaller sensors, simple I/O modules, or non‑critical operator panels, the replacement cost is low enough that extended warranty premiums would rarely pay off.

In practice, many fleets end up with a mixed strategy.

Equipment World suggests purchasing extended warranties on mission‑critical or technologically complex machines while self‑insuring simpler or low‑hour units. The same approach works well for automation: cover the expensive, central components that can shut down operations and accept the risk on low‑cost or peripheral devices.

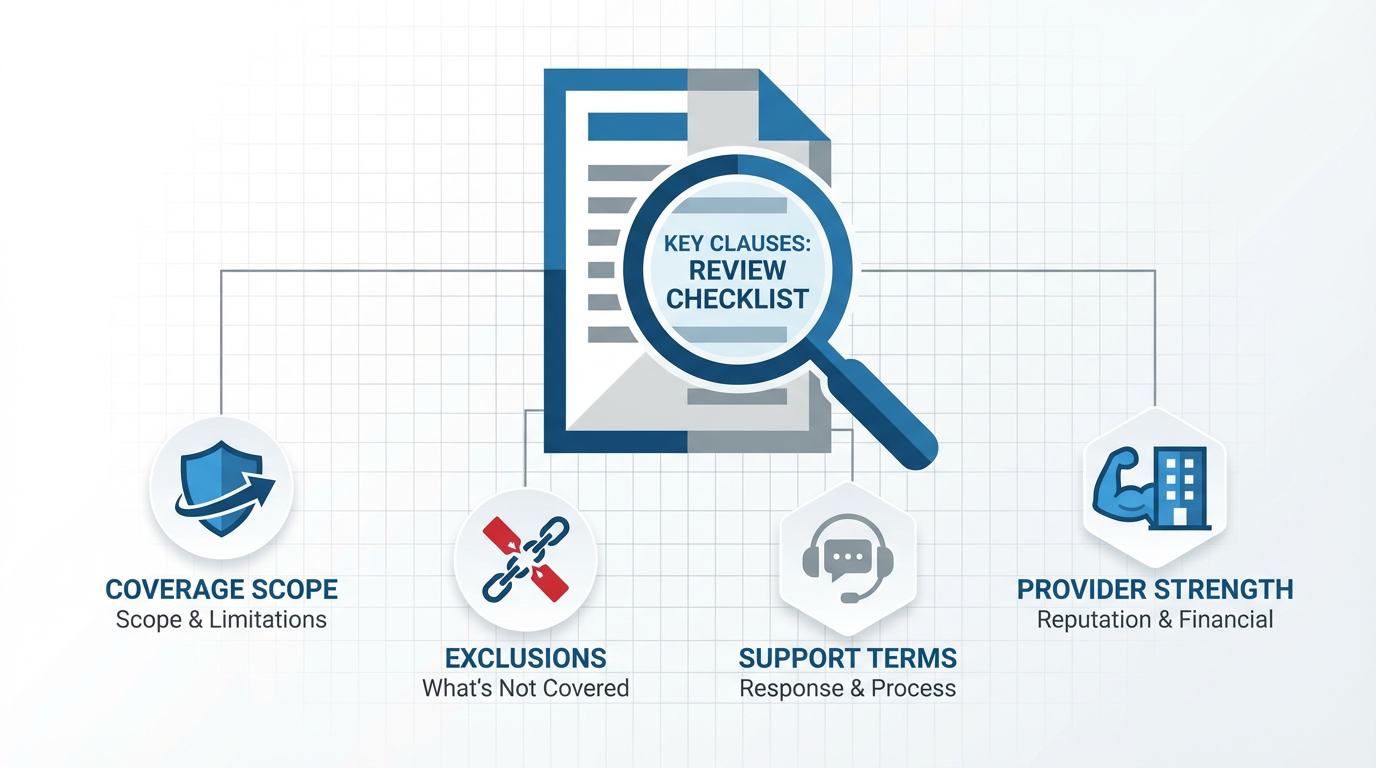

Key Clauses to Scrutinize Before You Sign

The difference between a useful extended warranty and a frustrating one often comes down to details in the contract. Qviro, Liberty Insurance, Equipment Dealer Magazine, Consumer Reports, and LinkedIn guidance on comparing contracts collectively point to a common set of clauses that deserve close attention.

You need to understand the official start and end dates. Qviro stresses that buyers should confirm whether coverage starts at shipping, delivery, or installation, especially for long‑lead projects. If you buy a production line today but commission it six months later, a warranty that starts at shipment could be half used before you produce a single part. Extended OEM warranties and ESCs may start immediately after base coverage or overlap; you need clarity to avoid gaps or wasted overlap.

Scope of coverage is the next critical area. Qviro recommends capturing, in writing, whether the warranty covers only parts or also labor, travel, shipping, and remote support. Liberty Insurance notes that EPPs may cover internal mechanical and electrical breakdowns and sometimes wear and tear, but usually exclude consumables, cosmetic issues, misuse, and external perils. Heavy equipment parts guides and Gregory Poole’s overview emphasize that most warranties exclude consequential damages such as collateral damage, lost revenue, or downtime costs. If a drive fails and damages downstream equipment, the plan may cover only the drive.

Usage limits and conditions also matter. Equify Financial points out that extended warranties often impose maximum coverage periods and meter‑hour restrictions. GT Mid Atlantic describes eligibility thresholds based on equipment age and hours, with additional tests for higher‑hour machines. In automation, the equivalents are operating‑hour limits, cycle counts, or duty‑cycle conditions. Exceeding these can reduce or void coverage.

Response and support terms shape the real value of the warranty. Qviro advises buyers to clarify expected response times, whether troubleshooting is remote or on‑site, and whether travel is billable. Construction Business Owner and Gregory Poole both highlight that good programs combine coverage with fast, dealer‑level service, including loaners or rental support. Without clear commitments, you may end up technically covered but practically stuck waiting while your line is down.

Exclusions and void conditions need to be read word for word. Consumer Reports underscores how extended service plans can include many fine‑print exceptions that let providers deny claims. Qviro and Liberty Insurance list common exclusions around misuse, lack of maintenance, unauthorized repairs, and off‑spec use. Equipment Dealer Magazine adds that some ESCs require OEM parts and dealer installation to remain valid. If your plant regularly uses third‑party repair houses or aftermarket components, you must factor that into plan selection.

Finally, the administration and financial strength of the provider are important. Equipment Dealer Magazine notes that ESCs are often administered by insurance or finance companies rather than OEM warranty teams. My‑Equipment stresses the need to evaluate the strength of the entity backing the warranty and to perform background checks on third‑party providers to avoid hidden fees or claim denials. OnPoint Warranty’s guidance to OEMs makes clear that extended warranties are a profit tool for manufacturers, which is a reminder for buyers to negotiate from an informed position.

The table below can serve as a quick review checklist when evaluating extended options for automation components.

| Clause or topic | What to confirm in writing | Why it matters for industrial components |

|---|---|---|

| Start and end dates | Exact trigger (shipment, delivery, installation) and termination date | Avoid wasting coverage before commissioning or leaving gaps later |

| Coverage scope | Parts, labor, travel, shipping, remote support, and software | Ensures major cost drivers and practical support are covered, not just hardware |

| Usage and conditions | Operating hours, cycles, environment, maintenance requirements | Protects against surprise denials for “off‑spec” use or skipped maintenance |

| Exclusions and limitations | Misuse, surges, third‑party parts, collateral damage, consumables | Clarifies what you still self‑insure even with an extended plan |

| Support model | Response times, on‑site vs remote, loaners, approved service network | Determines actual downtime impact when a covered failure occurs |

| Provider and administrator | Who holds the risk and pays claims, financial strength, track record | Reduces risk of non‑payment, disputes, or provider exit during your coverage |

Building a Practical Warranty Strategy into Lifecycle Planning

Extended warranties work best when they are part of a deliberate lifecycle and risk strategy, not an emotional decision at the end of a sales call. Several of the sources provide guidance that can be adapted directly to industrial components.

My‑Equipment suggests assessing your current repair and maintenance budgets, your formal risk management approach, your risk appetite, and your economic resilience before purchasing extended coverage. In an automation context, that includes an honest look at your failure history for PLCs, drives, robots, and safety systems; your spare‑parts strategy; and your ability to absorb a large, unexpected repair or replacement without disrupting capital plans.

Liberty Insurance recommends conducting a cost–benefit analysis for high‑value equipment, matching plan tiers to critical components, and coordinating EPPs with property and interruption insurance. For industrial components, a similar analysis might compare the cost of extended coverage on a set of drives against the expected cost and probability of failures over the planned ownership period, considering both parts and downtime. If you are already carrying business interruption insurance, you may choose to aim warranties more at repair costs and less at downtime coverage.

Itefy’s guidance on treating machinery acquisition as a structured decision and implementing formal equipment management systems fits naturally here. If you use a computerized maintenance management system or asset management platform, you can track warranty coverage periods for major components, log installation dates, and attach documentation such as purchase receipts, installation records, and maintenance logs. Construction Equipment and Qviro both stress that complete documentation and adherence to claim procedures are prerequisites for successful warranty claims. A structured system makes that manageable across many assets.

From a procurement perspective, LinkedIn guidance on comparing equipment warranties and service contracts suggests benchmarking duration, scope, cost, service quality, and flexibility against industry norms. For industrial components, that can involve comparing multiple vendors’ extended offerings for similar controllers or drives, and evaluating them side by side on coverage, response model, exclusions, and price rather than on a single headline term.

Finally, OnPoint Warranty’s advice to OEMs on using extended warranties to drive revenue, loyalty, and customer lifetime value is a reminder to buyers: these programs are designed to be profitable for the provider. That does not mean they lack value for you, but it does mean you should negotiate terms, ask for full written documentation up front, and treat extended coverage as one lever in a broader risk‑management framework rather than an automatic add‑on.

Short FAQ: Extended Warranties for Industrial Components

Should I buy extended warranties on all PLCs, drives, and robots?

In most plants, the answer is no. Qviro and Equipment World both imply that extended coverage makes the most sense for high‑value, intensively used, or process‑critical equipment. That usually means central controllers, primary motion systems, and robots that can stop production if they fail. For low‑cost, easily replaced items such as small I/O modules, basic sensors, and some HMIs, the premium for extended coverage often exceeds the likely benefit. A mixed strategy, where you cover the high‑impact components and self‑insure the rest, tends to be more cost‑effective.

How should I budget for extended warranties in a new automation project?

A practical approach is to treat extended warranties as part of total cost of ownership, not as an afterthought. My‑Equipment recommends assessing your current repair budgets and risk appetite, while Liberty Insurance encourages cost–benefit analysis for high‑value assets. When you build your project budget, estimate the cost of extended coverage on critical components over the planned ownership period and compare that to realistic failure scenarios for those components, including both parts and downtime. Fold the chosen coverage into your capital and operating budgets from the start rather than trying to bolt it on later.

Are third‑party extended warranties as safe as OEM extended warranties?

They can be, but due diligence is essential. Equipment Dealer Magazine notes that Extended Service Contracts are typically administered by insurance or finance companies rather than OEM warranty teams, and My‑Equipment stresses the need to evaluate the strength of the entity backing the warranty. Consumer Reports highlights that some third‑party automotive service plans have generated many complaints about claim denials. For industrial components, you should review the provider’s financial stability, claims history, and reputation, verify that your preferred service partners are authorized, and study the fine print on exclusions before assuming third‑party coverage will behave like OEM coverage.

What can I do to avoid claim denials on industrial components?

The research converges on several practices. Qviro, Liberty Insurance, and Construction Equipment all emphasize following manufacturer installation and maintenance instructions, using approved parts and service providers, and maintaining complete documentation. That includes purchase receipts, installation records, maintenance logs, and evidence of failure. Consumer Reports and heavy equipment guides both show that providers often rely on fine‑print exclusions when denying claims, which means compliance and documentation are your best defenses. Treat these requirements as part of your maintenance process, not as paperwork to be assembled later under time pressure.

Closing Thoughts

Extended warranties for industrial components are not a substitute for good engineering and disciplined maintenance. They are a financial and operational tool that, when chosen carefully and aligned with your plant’s risk profile, can support uptime, stabilize budgets, and make life easier when inevitable failures occur. As a systems integrator and project partner, I have seen extended coverage save projects and I have seen it disappoint when the fine print outweighed the promise. The more you treat warranty decisions as part of your overall asset and risk strategy, grounded in clear definitions and hard questions, the more likely you are to end up on the right side of that line.

References

- https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/30368/PDF/1/play/

- https://www.consumerreports.org/money/extended-warranties/buying-guide/

- https://www.smacna.org/docs/default-source/resource-documents/equipment-warranty-options-for-residential-contractors-white-paper.pdf?sfvrsn=6caa8e52_1

- https://blog.safeware.com/understanding-manufacturer-warranties-whats-covered-and-whats-not

- https://www.boomandbucket.com/blog/heavy-equipment-warranties-attract-buyers--increase-resale-prices?srsltid=AfmBOorGxeaG14DT2rdVFSSNki6hUuSjX4xITMdufkANSXTrYtOwv362

- https://www.constructionbusinessowner.com/equipment/4-tips-protect-your-machine-investment

- https://constructionequip.com/heavy-equipment-parts-warranty-coverage/

- https://equifyfinancial.com/heavy-equipment-warranty/

- https://www.equipmentdealermagazine.com/extended-warranty-vs-extended-service-contracts-whats-the-difference/

- https://www.gregorypoole.com/role-warranty-support-selecting-parts/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment