-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Industrial Asset Recovery Services: Turning Retired Equipment into Reliable Value

When you have spent years integrating control systems, commissioning drives, and fighting downtime on plant floors, you stop seeing “old equipment” as junk. You see tied‑up capital, hidden risk, and missed opportunities. Asset recovery services exist to turn those retired panels, motors, and servers back into working value instead of letting them rust behind the warehouse.

Across manufacturing and other asset‑heavy industries, downtime already costs thousands to millions of dollars per incident according to industrial asset management practitioners at Aetos Imaging. Poor maintenance alone can cut productive capacity by up to 20%, as reported by Deloitte and cited in lifecycle management work from Fieldpoint. On top of that, the Reverse Logistics Association estimates that companies with formal asset recovery programs can recapture roughly 3–5% of their capital expenditure every year, and the Investment Recovery Association has documented cases where professional recovery returns more than $20 for every $1 invested.

From a veteran systems integrator’s perspective, that is not optional value. It is the difference between a constrained capital budget and the ability to fund your next modernization.

What “Asset Recovery Services” Really Mean in an Industrial Context

In simple terms, industrial asset recovery is the structured process of identifying, evaluating, and monetizing surplus or end‑of‑life equipment so that you reclaim value, reduce risk, and avoid waste. It covers everything from spare VFDs and PLC racks to process skids, machine tools, and even entire production lines.

Several related terms show up in the literature. Investment recovery focuses on maximizing financial return from surplus assets. Asset disposition is the broader process of retiring assets through resale, redeployment, donation, recycling, or scrapping. IT asset disposition, or ITAD, is a specialized branch dealing with data‑bearing equipment like servers, HMIs, and network gear. Industrial asset recovery services bring these ideas together and apply them to plant equipment, often bundling project management, logistics, valuation, compliance, and resale into one offering.

Done well, asset recovery is not an emergency clean‑out at the end of a project. It is the controlled final phase of your asset lifecycle strategy, tied back to the same planning, CMMS data, and reliability thinking you use to justify new equipment in the first place.

Why Asset Recovery Belongs in Your Plant Strategy

Idle equipment is expensive. Okon Recycling highlights that storage in the United States often runs around $6.50 per square foot per month. When that square footage is filled with obsolete gear, you are paying rent and overhead for capital you no longer use. Spartan Capital notes that you still insure and sometimes maintain that equipment, even though it contributes nothing to throughput.

Asset recovery directly addresses that drag. APS Industrial cites Reverse Logistics Association figures showing that structured programs can recapture 3–5% of replacement capital annually by removing surplus equipment from the balance sheet, freeing space, and avoiding ongoing carrying costs. The Investment Recovery Association, referenced by INV Recovery, goes further and observes that well‑run programs can return over $20 for every $1 invested in professional recovery. Okon Recycling reports that, in some cases, simply applying an asset recovery program to outdated servers allowed a technology company to recover up to 28% of the original purchase value.

The financial benefit is only part of the story. INV Recovery points out that firms waste additional money and risk on security, storage, and compliance when idle assets are left unmanaged. World Economic Forum data cited in their research shows global e‑waste reaching about 62 million tonnes in 2022, which is roughly 68 million tons, and forecast to reach around 82 million tonnes, or about 90 million tons, by 2030, with barely more than a fifth formally collected and recycled. Every industrial asset that is reused, resold, or responsibly recycled instead of landfilled contributes to ESG goals and reduces long‑term environmental liability.

From years of plant closures and line changeouts, I have seen an additional effect: decision speed. When leadership knows there is a reliable recovery service ready to take decommissioned equipment and convert it into cash or credits, they move faster on control upgrades and equipment standardization. Asset recovery lowers the political and financial friction around modernization.

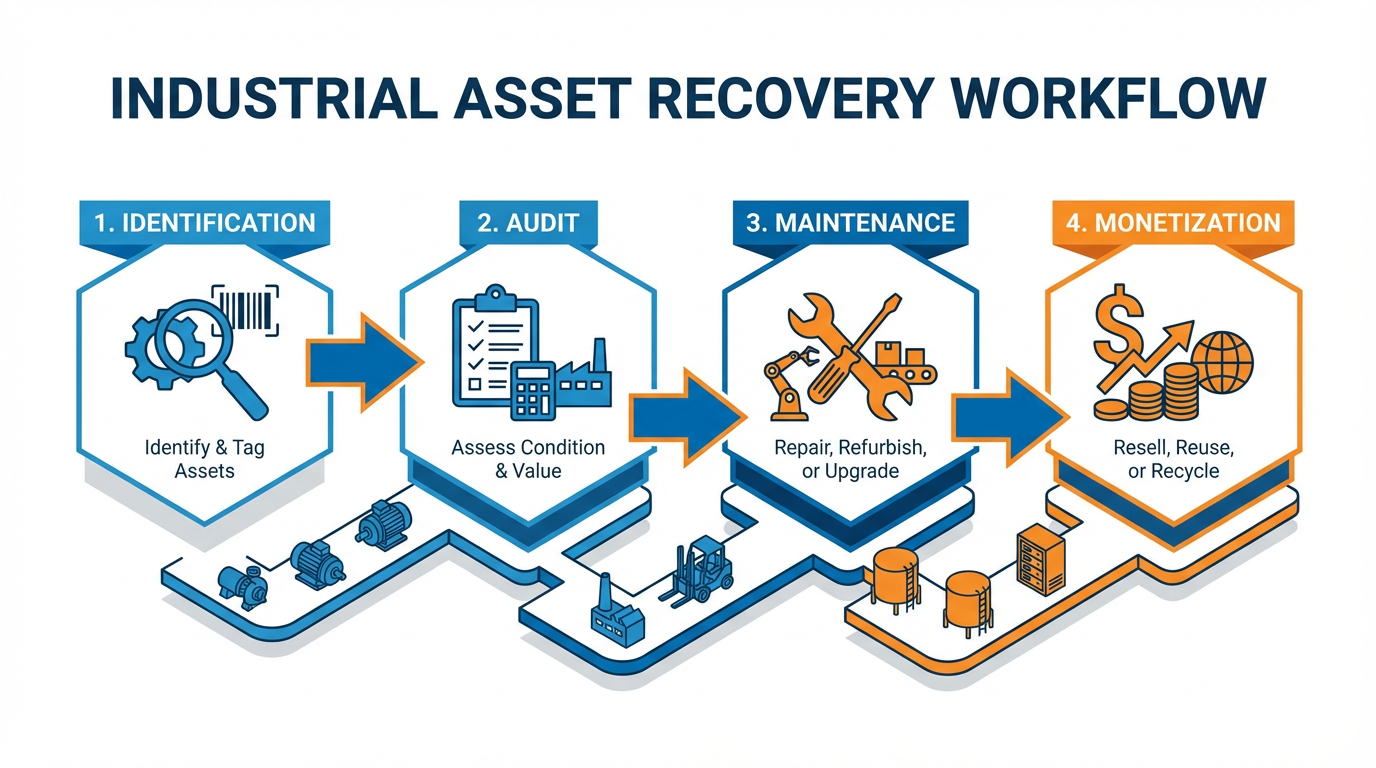

How Asset Recovery Services Work in Practice

Across many sources, including AFPlus, INV Recovery, APS Industrial, and Okon Recycling, the process converges on a predictable structure. Good providers execute that structure with discipline rather than improvising at the dock door.

From Identification to Close‑Out

The first stage is identification. Regular audits, walk‑throughs, and CMMS or ERP reports are used to flag equipment that is idle, under‑utilized, near end of life, or made redundant by new projects. APS Industrial and Okon recommend criteria such as assets not used for six months or more, utilization below a defined threshold, technology that is no longer supported, or inventory beyond safety stock. In multi‑site operations, this identification step is where a lot of value is lost if data is scattered in spreadsheets instead of centralized systems.

Next comes evaluation. Providers gather details on make, model, serial number, age, condition, maintenance history, and location. INV Recovery’s framework, drawing on investment recovery and accounting standards, stresses the importance of combining this internal data with market intelligence from auctions, dealer quotes, and price indices, while also factoring in environmental or remediation costs. The goal is a grounded view of residual value, not wishful thinking.

Segregation follows. Assets are grouped based on condition, compliance constraints, contamination, data sensitivity, and disposition path. In industrial practice, that might mean separating clean spare drives from oil‑contaminated gearboxes, or isolating data‑bearing control servers from non‑smart devices. Proper segregation avoids cross‑contamination and ensures that data‑secure processes are applied to the right items.

Finally, there is disposition and close‑out. Equipment is sold via auctions, marketplaces, brokers, direct sales, or internal redeployment; non‑saleable assets are recycled or scrapped. INV Recovery emphasizes the importance of close‑out and reporting: documenting financial outcomes, compliance steps, ESG metrics like landfill diversion and carbon savings, and feeding lessons learned back into procurement and design.

In my experience, the “close‑out” phase is the piece plants are most likely to skip. Six months later, someone asks what happened to a specific MCC or robot, and nobody can prove where it went. A disciplined recovery provider prevents that.

Evaluation, Valuation, and Channel Strategy

Valuation is where professional asset recovery firms earn their keep. INV Recovery recommends a multi‑step approach: collect all asset and cost data, assess markets through auctions and dealers, overlay regulatory and remediation expenses, and run financial models that incorporate storage, refurbishment, relocation, and opportunity cost. Final decisions are then reviewed with finance and environmental, health, and safety teams so they align with accounting standards such as IAS 16 derecognition.

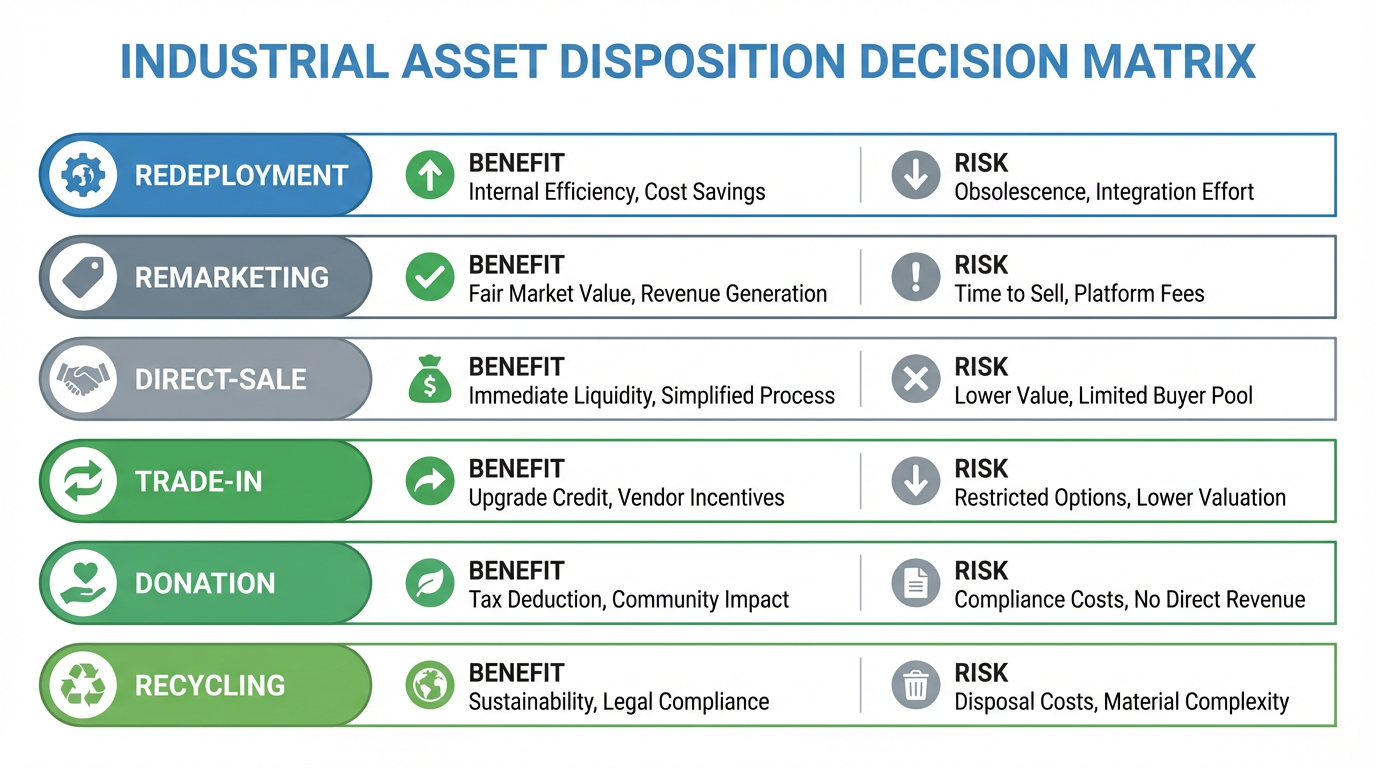

The right sales channel depends on the asset and your priorities. INV Recovery, APS Industrial, Amplio, and Southern Fabricating Machinery Sales collectively describe a set of options. Competitive auctions are effective for large volumes or tight timelines. Brokers and industrial liquidators are suitable for complex or specialized equipment when you need turnkey handling. Online industrial marketplaces work well for self‑service sellers with time to optimize price. Internal redeployment or cannibalization often delivers near‑100% “ROI” because you avoid new purchases entirely. Certified scrap and recycling are the route of last resort, used when there is no viable market but material value remains.

What matters from a plant manager’s standpoint is matching each asset to the right exit path rather than defaulting to whatever your local scrap buyer prefers.

Data, Documentation, and Compliance

For any equipment that touches data, asset recovery is inseparable from security and compliance. Research from Growrk and Telecom Recycle on IT asset recovery highlights NIST SP 800‑88 as the reference standard for data sanitization. Techniques range from software wiping and cryptographic erasure to degaussing and physical destruction, with the key rule that nothing is redeployed, resold, or recycled without verifiable erasure and a formal certificate of destruction.

Regulatory risk is not theoretical. INV Recovery’s work on asset recovery services cites numerous examples from adjacent domains. Under HIPAA, civil penalties for mishandling protected health information range from $141 up to $2,134,831 per violation, with criminal penalties that can include prison terms up to 10 years and fines up to $250,000. GLBA enforcement can involve institutional fines up to $100,000 per violation and $10,000 for responsible officers. Morgan Stanley paid about $60 million in 2020 after regulators found improper IT disposal, and Home Depot paid about $28 million in 2018 in a data breach case connected to vendor practices. Even if your plant is not handling medical records, the message is clear: losing control of data during equipment disposition is costly.

Environmental law is no softer. Asset disposition guidance from INV Recovery references RCRA and the Basel Convention, which from January 1, 2025, impose tighter controls on hazardous e‑waste and cross‑border shipments. Clean Air Act violations can reach over $100,000 per day per violation. In this context, certifications like R2v3 and e‑Stewards, which build on standards such as ISO 14001 and RIOS, are more than badges. They codify environmental, safety, and data‑security practices, require independent audits, and, in the case of e‑Stewards with NAID AAA, even include GPS tracking and unannounced inspections.

A good industrial asset recovery partner will bring ITAD‑grade controls into the plant for anything with storage or connectivity: historian servers, control panels with embedded drives, SCADA workstations, and even smart field devices. That is exactly where many plants are still weakest.

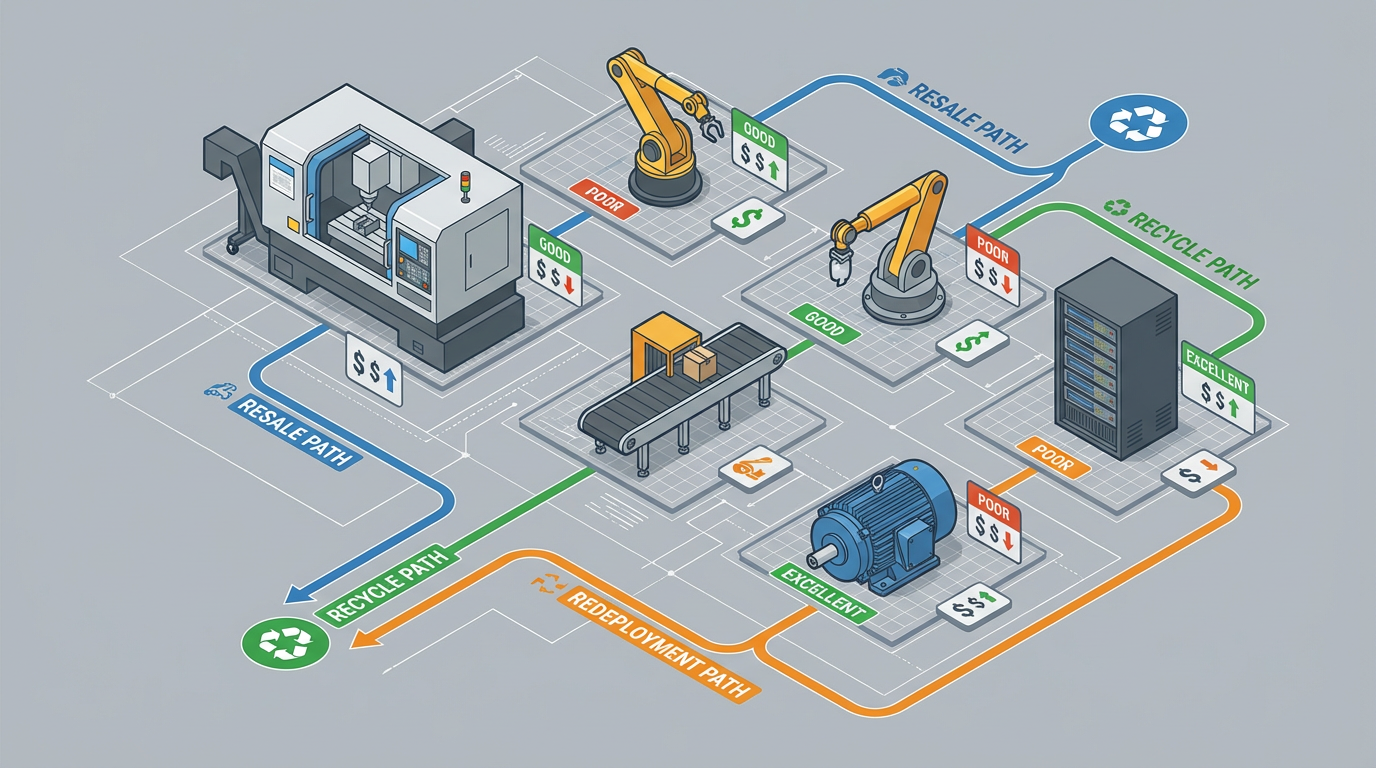

Disposition Paths for Industrial Equipment

Industrial asset recovery is not a single decision; it is a set of options that should be matched to the specific asset, business priorities, and risk profile. Okon Recycling, SurplusLoop, APS Industrial, Amplio, Southern Fabricating Machinery Sales, and Spartan Capital all describe similar patterns that can be summed up in a few common paths.

Here is a concise view of the main routes for industrial equipment:

| Disposition path | Best fit scenarios | Main advantages | Key tradeoffs and risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal redeployment and reuse | Standard or compatible equipment that other sites or lines can use, such as spare drives, motors, or instrumentation | Avoids new capex, keeps known equipment in service, shortens lead times, supports resilience | Requires accurate inventory and coordination; can mask over‑standardization issues if you keep redeploying unsupported gear |

| Professional remarketing, liquidation, or brokered sale | High‑value, specialized, or large equipment, or plant‑wide programs where internal capacity is limited | Access to wider buyer networks, professional valuation, turnkey logistics, faster cash conversion | Commissions and fees apply; quality of outcome depends heavily on provider capability and market timing |

| Direct sale or online marketplace | Well‑understood assets with clear documentation and moderate urgency, often in smaller lots | Maximum control over pricing and counterparties, ability to target niche buyers | Consumes internal time, requires marketing and negotiation, and can extend project timelines if not well managed |

| Return to vendor or trade‑in | Equipment with OEM buyback or trade‑in programs, especially controls, drives, and IT hardware | Can reduce taxable amount of new purchases, simplify logistics, and sometimes avoid capital gains on fully depreciated assets, as Southern Fabricating notes | May not maximize top‑line price; terms are set by OEM programs and can shift with market conditions |

| Donation and community reuse | Safe, functional equipment with limited resale value but strong educational or community use, such as training hardware and lab gear | Potential tax benefits, goodwill, and local impact, highlighted in Rheaply’s circular‑economy guidance | Still requires secure data removal, logistics, and documentation; not all equipment is suitable or welcome |

| Certified recycling and scrapping | Equipment that is obsolete, damaged, or non‑functional, but contains recoverable materials | Reduces landfill, recovers metal value, supports ESG goals; RJ Industrial and Okon demonstrate how scrap programs can offset decommissioning costs | Lowest financial recovery on a per‑asset basis; requires proof of compliant handling to avoid environmental and brand risk |

In a real project, you will often use several of these paths in one program.

The key is to decide path by path, based on data and risk, instead of pushing everything down the same chute.

Financial Reality Check: What the Numbers Tell Us

Asset recovery can feel theoretical until you look at the aggregate. APS Industrial cites Reverse Logistics Association analysis showing that firms with formal programs recapture 3–5% of their annual replacement capital by systematically identifying and monetizing surplus equipment. INV Recovery reports that data from the Investment Recovery Association shows more than $20 returned for every $1 invested in professional asset recovery services in some programs, compared with minimal value from ad‑hoc disposals.

Lifecycle timing matters as well. INV Recovery’s work on IT and medical assets notes that IT hardware can retain 80–90% of its value in the first year, 60–75% in years two and three, 40–60% by years four and five, and only about 15–30% beyond that. While heavy industrial machinery behaves differently, Okon Recycling observes that well‑maintained equipment can realize 15–25% higher recovery values than poorly maintained equivalents. This aligns with Fieldpoint’s emphasis that proactive maintenance extends usable life and preserves performance.

There is also real money inside the scrap stream. INV Recovery highlights that servers alone can yield about 15–50 in recoverable metals per unit, and recycling one million cell phones can recover approximately 35,000 pounds of copper, 772 pounds of silver, and 75 pounds of gold. The same physics apply to drive cabinets, bus duct, and process equipment full of copper and aluminum.

On the risk side, IBM’s research on data breaches cited in Growrk’s hardware disposal analysis puts the global average cost of a breach at roughly $4.35 million, with figures reaching about $9.44 million in the United States. Other studies referenced by INV Recovery indicate that average global breach costs increased from about $4.45 million in 2023 to roughly $4.88 million in 2024. From an industrial automation standpoint, those numbers should be attached in your mind to any control server or historian leaving the building without proper erasure and documentation.

As a practical rule, the plant that plans asset recovery six to twelve months before major retirements, as recommended in INV Recovery’s asset recovery services guidance, and treats it as a value driver rather than a cost of doing business, will consistently have more capital to invest in modernization than the plant that leaves everything to the last month of the project.

Risk, Compliance, and Data Security: The Non‑Negotiables

Every source that looks seriously at end‑of‑life equipment arrives at the same conclusion: unmanaged risk can wipe out all of the financial gain from asset recovery and more. INV Recovery’s regulatory overview shows how environmental rules under RCRA, international controls such as the Basel Convention, and U.S. air‑quality laws with penalties above $100,000 per day create a hard floor under environmental compliance.

On the data side, Growrk, Telecom Recycle, and IT Asset Management Group all emphasize standardized data destruction aligned with NIST SP 800‑88, serialized certificates, and chain‑of‑custody documentation. NAID AAA certification, referenced in INV Recovery’s coverage of e‑Stewards, requires background‑checked staff, strict access control, and at least $2 million in general liability coverage, along with GPS tracking in some cases.

For industrial facilities, this means treating data on control systems and historians with the same rigor as a corporate data center. That includes documenting which devices hold configuration files, recipes, batch records, and quality data; deciding whether to erase, destroy, or securely retain each storage device; and ensuring that your asset recovery provider has both the process and insurance to handle that exposure.

Risk management also extends to logistics and legal exposure. INV Recovery outlines how environmental liability under RCRA often follows strict joint and several standards, and notes that many programs require minimum environmental coverage around $1 million per occurrence and higher for ongoing exposure. In parallel, they point out that average breach costs in sectors like healthcare and financial services can reach tens of millions of dollars, driving demand for cyber and professional liability limits in the $5–10 million range for data destruction services.

From a systems integrator’s seat at the project table, my practical advice is straightforward. Do not sign off on a decommissioning plan that lacks clear answers on chain of custody, data sanitization methods, evidence of environmental compliance, and vendor insurance. If your integrator or recovery provider cannot show you sample certificates, manifests, and reports from prior projects, you do not have a mature risk posture.

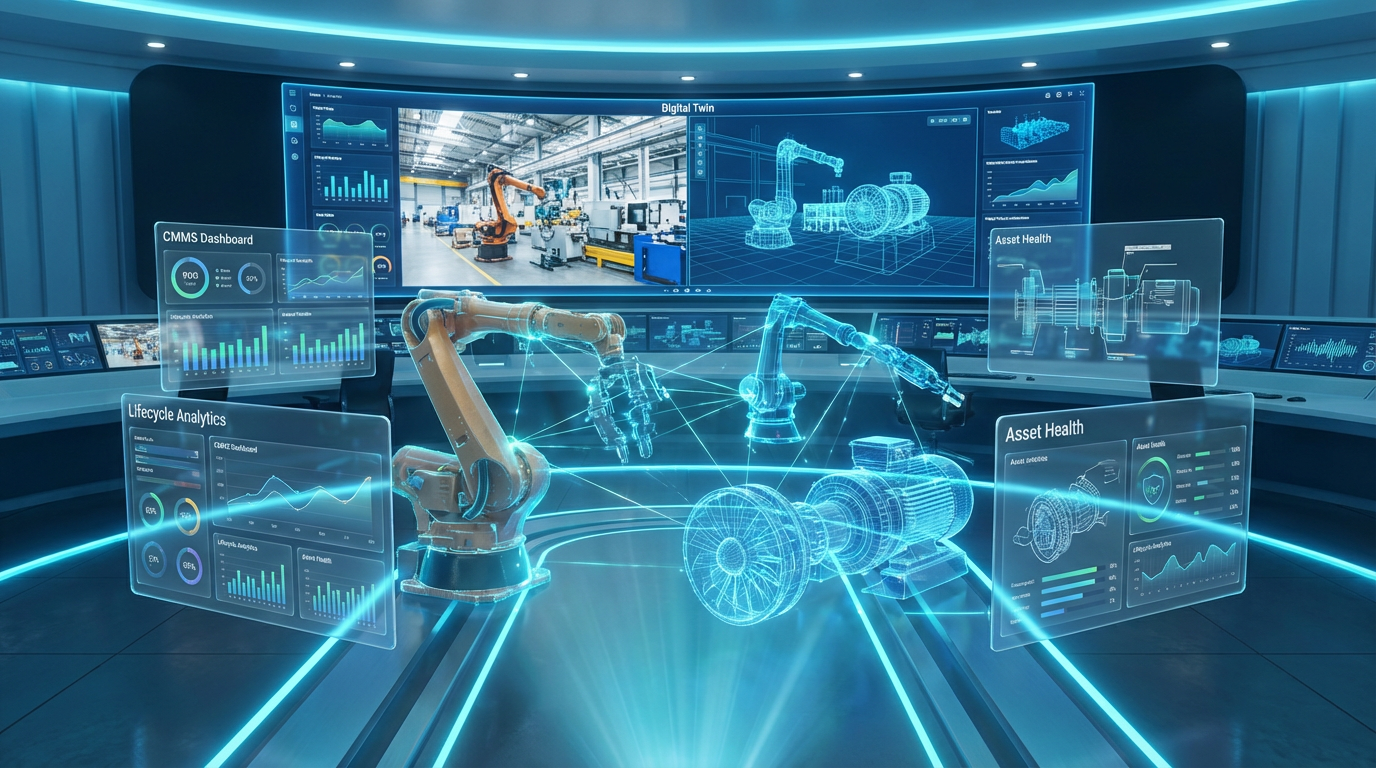

Integrating Asset Recovery with Asset Management and Lifecycle Planning

The best returns show up when asset recovery is not a standalone initiative but an integrated phase of your asset management strategy. Aetos Imaging and Fieldpoint both stress formal asset management systems, computerized maintenance management, and lifecycle thinking as the backbone of reliable operations. Rheaply, INV Recovery, and SurplusLoop extend that logic into investment recovery and circular economy practices.

In practice, this integration looks like a few concrete capabilities. You maintain a centralized, accurate inventory of equipment across plants, with location, condition, and utilization tied into your CMMS or ERP. Fieldpoint calls this equipment lifecycle management and frames it as a four‑stage loop: planning, acquisition, operation and maintenance, and renewal or disposal. Asset recovery is essentially the renewal or disposal stage with teeth.

You also track key reliability and performance indicators such as mean time between failures, mean time to repair, and overall equipment effectiveness, as recommended by Aetos and others. These metrics feed your decisions about which lines to modernize and which assets to retire. When the data shows chronic under‑performance, the “disposition” path should not be a scramble; it should immediately invoke a predefined recovery workflow.

Digital tools are increasingly central to this integration. Aetos describes the value of visual maintenance management systems and digital twins for seeing assets in context and supporting training. INV Recovery and SurplusLoop show how inventory tagging, analytics, and cloud platforms make it easier to locate surplus equipment, estimate market value, and choose between reuse, resale, and recycling. Rheaply’s work on asset disposition emphasizes platforms that match internal supply and demand first, then route remaining assets to external markets or community partners.

From a project‑delivery angle, I have found that the more your asset registry and maintenance history are digitized and trusted, the less time you waste walking yards with clipboards when it is time to plan a recovery program. Digital discipline pays off both in uptime and in recovery value.

Choosing and Managing an Asset Recovery Partner

Given the complexity of modern asset recovery, most industrial organizations benefit from working with specialized partners rather than trying to do everything in‑house. INV Recovery, IT Asset Management Group, Telecom Recycle, APS Industrial, Okon Recycling, Southern Fabricating, Amplio, and Spartan Capital all describe success factors that are remarkably consistent.

At a minimum, you want verifiable environmental and data‑security certifications where they apply. For IT and data‑bearing assets, that may include R2v3, e‑Stewards, NAID AAA, and ISO 14001 or 9001. INV Recovery notes that obtaining and maintaining R2 certification alone can cost around $100,000 per facility per year and take eight to twelve months, which is why many organizations prefer to leverage specialist providers rather than build that capability internally.

You also need evidence of financial strength and risk management. INV Recovery suggests reviewing audited accounts or commercial credit ratings and confirming that providers carry appropriate general, environmental, cyber, and professional liability coverage at limits consistent with your risk profile. For large industrial programs, combined limits of several million dollars are common.

Service range and geographic reach matter as well. The best partner for a data‑center‑heavy portfolio may not be the right one for plant demolition and heavy rigging. RJ Industrial positions itself as a full‑service provider for industrial decommissioning and scrap metal recycling, while Amplio and APS Industrial focus on rapid asset recovery through redeployment, liquidators, auctions, and online marketplaces. Telecom Recycle and IT Asset Management Group emphasize ITAD and data‑center decommissioning.

Finally, governance and communication determine whether the partnership actually works. INV Recovery and Growrk recommend treating asset recovery as a cross‑functional effort with Legal or Compliance, Finance, Procurement, ESG, and Operations all at the table. Clear performance metrics such as recovery rate, net proceeds, storage cost reduction, e‑waste diversion, and documentation completeness keep everyone aligned.

In my own projects, the best outcomes have come when asset recovery partners were engaged during early design and planning, not after the last product shipped.

That early involvement lets them advise on layout decisions, staging, and packaging that simplify removal and maximize recovery later.

Lessons from the Field: Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Walking through numerous decommissioning and modernization projects, a few patterns repeat themselves whenever asset recovery underperforms.

The first is late engagement. Waiting until a month before shutdown to involve recovery specialists usually forces everything through the fastest option instead of the most valuable one. Assets that could have been redeployed or resold end up in mixed scrap piles because there was no time to catalog them. INV Recovery explicitly recommends starting planning six to twelve months in advance for this reason, and that matches what I have seen on the ground.

The second is poor data. When equipment records are incomplete, inconsistent, or spread across multiple systems, you spend time reconciling basic details that should have been known instantly. Okon Recycling, APS Industrial, and Rheaply all stress centralized, accurate inventories for a reason. Without that, even the best external partner will struggle to unlock full value.

The third is treating all equipment the same. I have seen plants use scrap‑metal pricing as the benchmark for everything when, in reality, some assets had strong secondary markets that brokers or specialized marketplaces could have tapped. The case study from INV Recovery describing a Fortune 500 utility redeploying gas turbines internally and then auctioning ancillary parts for millions of dollars illustrates what disciplined channel selection can deliver.

The fourth is underestimating compliance and data risk. Growrk’s summary of IBM’s breach cost data and INV Recovery’s catalog of regulatory penalties show how quickly a mishandled storage device or undocumented shipment can erase the financial gains from a recovery program. The safest path is to assume that regulators and auditors will look closely at high‑value disposals and to build your documentation accordingly.

Finally, many teams treat asset recovery as a one‑time event rather than a continuous discipline. APS Industrial, Okon, and Rheaply all argue for making recovery part of standard decommissioning, end‑of‑project, and offboarding workflows. In my experience, when operators and maintenance technicians are trained to flag idle assets and know that a structured process exists, your pipeline of recoverable value becomes steady instead of sporadic.

FAQ: Practical Questions Plant Teams Ask

When does it make sense to bring in an asset recovery provider instead of just scrapping equipment locally?

Third‑party recovery adds value when the assets in question have meaningful residual value, complexity, or risk. Large drives, CNC machines, process skids, robotics, and data‑bearing control systems all fall into that category. Research from APS Industrial and INV Recovery shows that professional programs consistently outperform ad‑hoc scrap sales in recovery value, while also taking on a share of the logistics, marketing, and compliance burden. Local scrap outlets still have a role for truly end‑of‑life material, but they should be one tool among many, not the default for everything.

How early should we plan asset recovery for a major modernization or site closure?

Evidence from INV Recovery and IT Asset Management Group, along with lessons from industrial decommissioning specialists such as RJ Industrial, point to a six‑ to twelve‑month planning window before the first major asset is retired. That time allows for complete inventories, market analysis, scheduling of liquidations or auctions, and alignment with internal finance and compliance calendars. In practice, I recommend starting the planning conversation as soon as you approve the capital project, so that recovery and decommissioning are part of the same integrated plan.

How do we know if our current approach is leaving money on the table?

A simple diagnostic is to calculate how much you spent on capital equipment over the past year and how much you actually realized from surplus sales, excluding scrap sold by weight. If the return is well below the 3–5% of capex range cited by the Reverse Logistics Association and APS Industrial for structured programs, you likely have room to improve. You can also look at qualitative signs: lack of consistent documentation, uncertainty about where retired assets went, absence of chain‑of‑custody records, and ad‑hoc decisions about reuse or resale. Those are indicators that your process is reactive rather than controlled.

Closing

Asset recovery for industrial equipment is not a nice‑to‑have bolt‑on at the end of a project. It is a disciplined extension of the same engineering, lifecycle, and risk thinking you already apply to your control systems. When you treat it that way, backed by credible partners and data, you free capital, reduce risk, and clear the way for the next round of modernization. That is exactly the kind of reliable, project‑grounded value a seasoned systems integrator should help you deliver.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/5920092/White_Book_on_Best_Practices_in_Asset_Recovery

- https://flora.insead.edu/fichiersti_wp/inseadwp1997/97-35.pdf

- https://invrecovery.org/9-tech-driven-strategies-to-boost-your-surplus-asset-recovery/

- https://fieldpoint.net/how-to-better-manage-the-industrial-equipment-product-lifecycle/

- https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/2921031/NRI%20Solutions%20PC1%20Final%20-%20Approved-1.pdf

- https://aetosimaging.com/blog/15-best-practices-for-better-asset-management

- https://afplus.com/effective-strategies-asset-recovery/

- https://www.amplio.com/post/4-proven-strategies-for-rapid-asset-recovery

- https://www.apsindustrialservices.com/blog/asset-recovery-strategies-turn-surplus-equipment-materials-into-profit

- https://asertis.co.uk/seven-tips-for-successful-asset-recovery/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment