-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Understanding Return Policies for Automation Parts

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

I have lost count of how many projects came down to a single part. A drive that arrived with the wrong firmware, a safety relay that turned out to be the wrong variant, an I/O card that failed during startup. In every case, the technical issue was solvable. The real headache was what came next: negotiating a return with the supplier while a production line, a commissioning team, and a project budget were all on the line.

Return policies for automation parts are not a legal footnote. They are an operational control that affects uptime, safety, and margin. When they are vague, you pay in downtime, scrap, and soft costs. When they are clear and well designed, they protect relationships and help you recover value from inevitable mistakes and failures.

In retail and ecommerce, organizations like the National Retail Federation have been sounding the alarm for years. Industry research puts total US retail returns in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually and shows that a single return can cost up to sixty percent of the item’s sale price once transportation, handling, and discounts are accounted for. Studies cited by ecommerce operations platforms show online return rates in the twenty to thirty percent range, with reverse logistics becoming a major margin risk. While industrial automation volumes are much lower, the stakes per unit are much higher. A $2,000 drive or safety controller is not a pair of shoes.

This article takes lessons from those mature returns programs and applies them to the reality of automation hardware: control panels, PLCs, VFDs, safety devices, sensors, and spares that keep plants running. I will walk through how to interpret return policies, how to design your own internal rules as an integrator or OEM, and how to use returns data to improve reliability rather than simply eat cost.

The Real Cost of Returns in Automation

In ecommerce, analysts regularly quote figures showing that managing a single return can consume more than half the original sale value once you factor in transport, processing, restocking, and resale discounts. The National Retail Federation has reported retail returns on the order of $761 billion in 2022 and roughly $890 billion in 2024. Other research puts online return rates around a quarter of sales.

Those numbers come from consumer retail, but the physics of returns do not change when the product is a servo amplifier instead of sneakers. Someone still has to authorize the material, create labels, receive and inspect the unit, decide whether it is repairable, refurbish or scrap it, and update inventory. That work consumes scarce engineering and warehouse time. For automation parts, you also add the cost of downtime risk, safety documentation, and the possibility that a wrongly handled component ends up in a critical machine later.

Another consistent theme in the research is customer behavior. Multiple surveys show that most buyers read return policies before purchasing, and a majority will not buy again after a bad returns experience. One study cited by returns management vendors found that more than three quarters of consumers consider free and easy returns a key factor in where they shop, and another found that ninety six percent would buy again after an “easy” return. In automation, the audience is different, but the behavior is similar. Plant engineers and procurement teams remember who stood behind their product when it failed on startup and who hid behind fine print.

Finally, there is fraud and abuse. Research from Appriss Retail and the National Retail Federation estimated that about 13.7 percent of US retail returns, roughly $101 billion, were fraudulent. Another report put abusive or fraudulent returns at about 6.5 percent of return volume. In industrial automation the patterns are different, but the risks are real: boards swapped between units, mis-declared “dead on arrival” parts that were miswired, and counterfeit items entering your supply chain. A good return policy has to encourage legitimate returns and still give you tools to manage abuse.

Key Concepts: Warranty, Return Policy, RMA, and Reverse Logistics

Before you can evaluate a return policy, you need to be precise about the language. In many projects I have seen people use “warranty” and “return” as if they were interchangeable. They are not, and that confusion leads to expensive surprises.

Warranty vs. Return Policy

A warranty describes what the manufacturer will do if a product fails under specified conditions within a defined period. Typical industrial automation warranties, as outlined in generic industry guidance, cover a time period, define what counts as a defect, spell out how to get authorization, and list exclusions such as misuse, improper installation, or modifications. They often disclaim incidental or consequential damages such as lost production. The exact terms vary by vendor, which is why checking the actual document is essential.

A return policy, by contrast, governs when you can send a product back even if it is not defective. That includes incorrect orders, surplus stock after a project change, or items that are technically working but not suitable. The return policy defines windows, conditions, restocking fees, and who pays freight. A part can be perfectly healthy and still be non-returnable because it is custom, programmed, or out of time.

RMA and Parts Return Management

An RMA, or Return Merchandise Authorization, is the control mechanism that ties a specific physical item to a process. When a return is initiated, the supplier issues an RMA number and rules about packaging, documentation, and where to ship. Well-run organizations use that number all the way through receiving, inspection, testing, and disposition so no unit becomes a mystery box on a shelf.

In industrial sectors this is sometimes formalized as a parts return management program. A case study from an automotive OEM described by Intellinetsystem shows what that can look like: engineering teams raise structured return requests with serial numbers and failure codes, return centers validate and communicate with dealers and carriers, and technicians perform mechanical and software diagnostics to capture root cause data. That structure is what lets you turn returns into quality feedback rather than just a cost center.

Reverse Logistics in an Industrial Context

Reverse logistics is the physical movement side of returns: how items move from the field back through carriers, return hubs, and warehouses. In a modern automated warehouse, systems like AutoStore can bring bins containing returned SKUs directly to workstations in a dedicated return-inbound mode. The vendor reports capacity gains of up to four times compared with traditional shelving and emphasizes that faster return-to-stock and higher picking accuracy directly reduce return quotas and lost recovery value.

In automation hardware, reverse logistics often crosses borders and time zones. You may be returning drives to a regional repair center, shipping failed sensors back to Europe for analysis, or consolidating returns from a dealer network. The policy sets expectations; the reverse logistics design makes it feasible.

What Makes Automation Parts Returns Different

Returning a PLC or safety relay is nothing like returning a T-shirt. The stakes and complexities are higher in several ways.

First, the hardware is usually part of a larger system. A drive programmed with a specific configuration, a safety light curtain paired with a controller, or a custom I/O module for a proprietary rack is not necessarily resellable as new. Even if the component powers up, the supplier may not be able to guarantee traceability or safety if it has been wired, configured, or mechanically stressed.

Second, the impact of a failed or wrong part is magnified by downtime. In consumer ecommerce, the worst outcome is an unhappy customer waiting for a replacement. On a plant floor, a failed drive or misapplied safety relay can idle a line that generates tens of thousands of dollars per hour. That is why many integrators and OEMs keep critical spares on hand and only attempt returns once the process is stable.

Third, automation parts often carry firmware and software. A lot can happen between the time a product leaves the warehouse and the time it returns. Firmware may have been flashed, parameters changed, or nonvolatile memory written. For safety-rated and regulated equipment, the supplier may be required to treat any returned, energized device as used, which drives stricter return conditions.

Finally, there are compliance and safety responsibilities. If a device has been installed in a hazardous environment, exposed to process media, or used in a safety function, returning it may require decontamination, lockout tags, or additional declarations. A general-purpose ecommerce-style return policy will not capture those nuances.

Core Elements of a Solid Automation Parts Return Policy

Despite these differences, the building blocks of a good return policy are consistent. Retail-focused guides from companies like Shopify, WooCommerce, and Avalara describe similar core elements: eligibility, timelines, condition, cost allocation, exceptions, and clear instructions. In automation, each of those needs a technical twist.

Eligibility and Product Categories

The first question is what you can return at all. Most industrial suppliers treat stocked catalog items differently from configured or custom products. A standard sensor or relay in its original packaging may be returnable. A custom panel, software license, or special-order drive with engineered firmware usually is not.

Make sure the policy distinguishes between standard and non-standard goods and that your project teams understand the implications. If a proposal includes a long list of configurable part numbers, assume many of them will be non-returnable and plan ordering and spares accordingly.

Return Windows and Project Timelines

Industry research on ecommerce shoppers shows that about sixty three percent of customers expect at least a month to return an item, and roughly twenty three percent expect at least two weeks. In consumer channels, return windows of thirty, sixty, or ninety days are common. For automation parts you will often see much tighter windows on standard stock, sometimes thirty days from shipment, and no returns at all on custom gear.

This matters for project planning. If you buy all long-lead items nine months before commissioning, you cannot assume you will be able to return surplus drives or HMIs when the design changes during startup. I encourage teams to align procurement phasing with return windows for high-value items and to negotiate extended windows for major projects where possible.

Condition, Testing, and Repackaging

In every sector, policies emphasize that items must be in resellable condition. ClickPost and other returns platforms highlight the importance of clearly specifying expected condition, such as original packaging, tags attached, and no visible wear. For automation parts, “resellable” typically means untouched or at least not energized. Original packaging, terminals never wired, and no panel-cutouts or mounting marks.

If you need to bench test a component, consider ordering an extra unit specifically for testing and keeping it rather than risking the eligibility of the stock you plan to return. When you do return goods, follow packaging instructions carefully. Warehouse automation vendors note that secure packaging and accurate labeling reduce damage and handling cost; one study cited by AutoStore found that about thirty eight percent of customers value secure packaging for precisely that reason. In my own projects, a surprising number of rejected returns came down to nothing more than damaged boxes or missing accessories.

Shipping, Restocking, and Who Pays

Who pays freight and whether there are restocking fees are where many relationships sour. Retail research shows a tug of war: more than three quarters of consumers rate free returns as a top consideration when shopping online, yet surveys from Avalara and others report that about sixty six percent of retailers have begun charging for one or more return methods to control costs. Some charge shipping, others restocking, and many use store credit to soften the blow.

In automation, policies are often stricter. It is common to see restocking fees for unopened stock, higher fees for opened but unused items, and no returns for energized equipment unless the manufacturer confirms a defect. Make sure you understand the thresholds. A fifteen percent restocking fee on a $100 proximity sensor is annoying. The same fee on a pallet of drives is a line item in your project margin.

Non-Returnable and Special Cases

Most policies carve out categories that are non-returnable except under warranty. The research across multiple guides highlights typical examples: personalized or custom items, clearance goods, perishable or hygiene-sensitive products, and digital licenses. In automation, translate that to custom-engineered panels, cut-to-length cable assemblies, software and firmware licenses, and often safety-related components once installed.

You may also encounter “returnless refunds” for low-value items, a tactic used more in ecommerce. Returns automation providers describe this for goods where the shipping and handling cost exceeds resale value, often in the range of fifteen to forty dollars. For industrial distributors, this sometimes appears as “scrap in field” instructions on a failed low-cost device rather than returning it. Understand where this line sits for your suppliers.

Component Overview in Automation Context

A concise way to think about these elements is to frame them against practical questions you should be able to answer when reading a policy.

| Policy Component | Automation-Specific Question | Typical Pitfall |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | Is this part standard stock, configurable, or fully custom? | Assuming configurable or custom items are returnable |

| Time window | Does the clock start at shipment, delivery, or invoice date? | Buying far in advance of project milestones without flexibility |

| Condition | Can we test or mount this without voiding return eligibility? | Energizing or installing a part and then trying to return it |

| Costs and fees | Who pays shipping and what restocking percentage applies by category? | Discovering fees only after the project budget is committed |

| Exceptions and safety | Are safety or hazardous location devices treated differently? | Returning contaminated or safety-critical items improperly |

If a supplier’s policy does not let you answer these questions quickly, treat that as a risk and ask for clarification in writing.

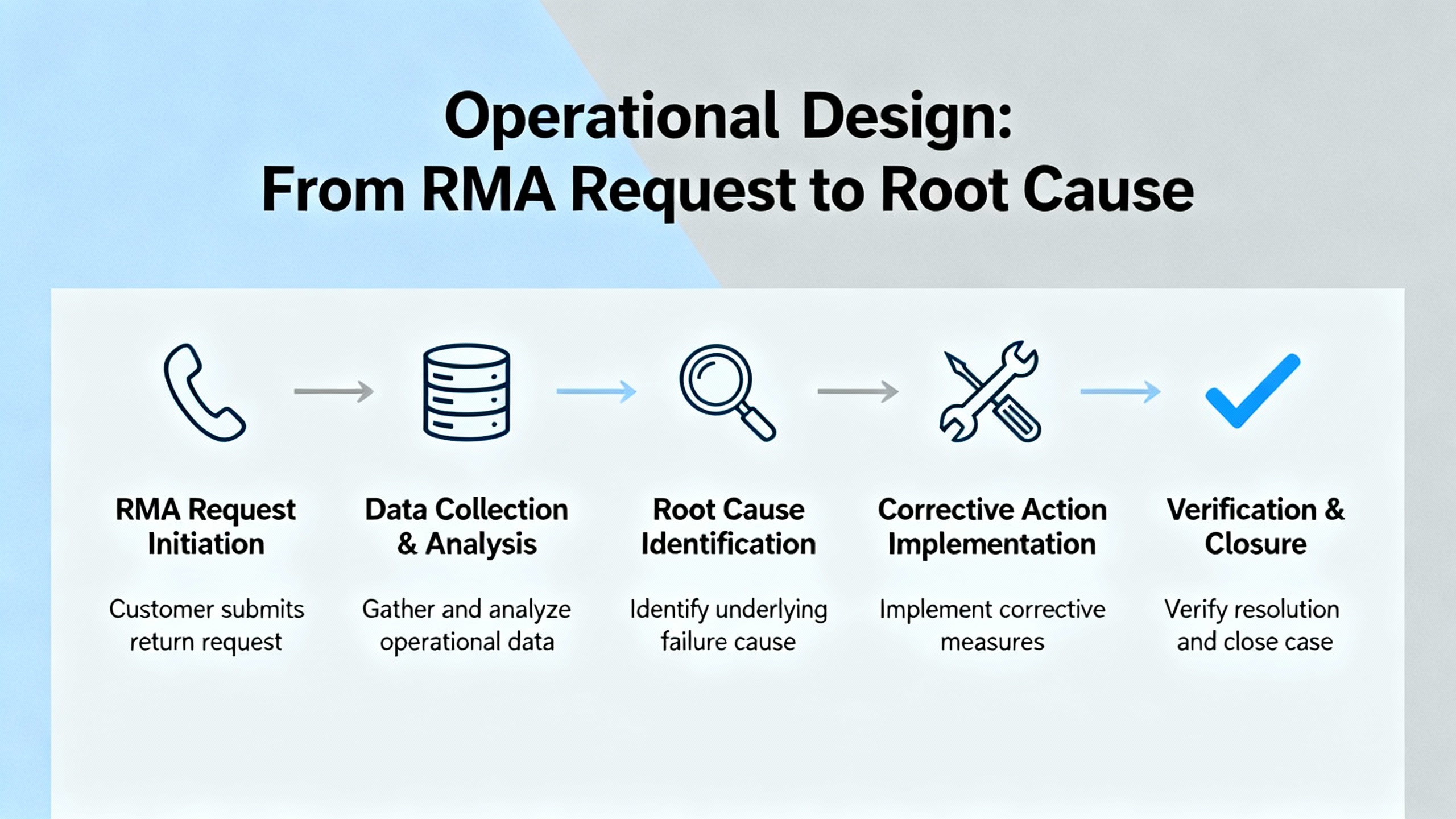

Operational Design: From RMA Request to Root Cause

In well-run ecommerce operations, experts describe returns management as a full workflow: initiation, decision, logistics, inspection, disposition, and outcome. A practical guide published by TechnologyAdvice lays this out in detail with standard operating procedures from RMA creation through restocking. The same logic applies cleanly to automation parts.

When a customer initiates a return, the process should be simple. A short online form, a contact in the distributor’s portal, or a message to your account manager that triggers an internal ticketing process are typical. At this point systems in mature organizations automatically check order date, eligibility, and basic risk flags. In my own work, I encourage clients to mirror this discipline internally: keep clear records of serial numbers and installation dates so you can make a well-documented case to your supplier if needed.

Once the request is in, the supplier decides whether to approve, deny, or offer an alternative such as repair. Retail research referenced by Loop and other automation vendors shows that many companies implement rules such as auto-approving low-risk cases and routing high-value or high-risk returns to manual review. For automation parts that might mean automatic approval for unopened catalog items within thirty days, and engineering review for expensive drives, safety equipment, or items with a history of misuse.

Shipping and logistics coordination follow. In ecommerce, best practice is to generate prepaid labels via carrier integrations and provide simple instructions. Some industrial suppliers already do this; others require you to arrange freight and mark the RMA number clearly. Either way, clarity of packaging instructions is crucial. AutoStore’s research highlights that accurate address data and labeling significantly reduce processing issues, and the same is true in a parts depot.

Inspection and grading at the return center is where engineering rigor matters. The ecommerce world often uses grading frameworks from A (resale-ready) through D (scrap or recycle). Industrial parts programs described by Intellinetsystem go further, with structured mechanical tests, software diagnostics, and detailed failure coding. For automation parts, I recommend asking your suppliers how they categorize returns and whether you can see summary data by grade. If most of your returns on a specific sensor family end up classified as “no fault found,” you have a very different problem than if they are consistently failing under load.

Disposition options come next. Resale-ready parts can return to stock. Some items may be repaired or refurbished and sold as remanufactured. Others go to secondary channels or recycling. A returns management system like the one described in the automotive case study can automate these routes and give visibility into where value is recovered or lost. AutoStore-style warehouse automation can then put returned items back into pickable inventory in the same shift, which shortens the interval between return and revenue.

The final customer-facing step is the outcome: refund, credit, or replacement. Here, research in the Journal of Marketing is worth noting. One study found that making returns easy can increase customer purchases over the following two years by between fifty eight and three hundred fifty seven percent. Other surveys show strong repeat purchase intent after easy returns. In automation, that translates to integrators and plants who stick with suppliers that resolve issues quickly and predictably, even when a project has gone sideways.

Using Data and Automation to Improve Returns

Across almost every research source, one theme is consistent: organizations that systematically track return reasons and timelines outperform those that treat returns as random noise. A logistics study cited by Meteor Space contrasted online and physical return rates around thirty percent and about 8.89 percent respectively, pointing to the cost of poor product information. Another survey reported that eighty two percent of online shoppers are influenced to purchase by a retailer’s return policy, while other research found that eighty three percent of customers say detailed product information has the greatest impact on their purchase decisions.

For automation suppliers and integrators, this data lens is invaluable. If a particular batch of drives generates many “overcurrent fault” returns within a short period, that is a hint of a design or application issue. If a certain sensor model sees frequent “wrong type ordered” returns, that may be a catalog clarity problem rather than a quality issue. In the automotive case study implemented with Intelli RMS, the OEM used structured return data to identify recurring failures and feed that insight back into design and sourcing decisions.

Warehouse automation adds another layer. AutoStore reports that by improving storage density and automating bin delivery to workstations, they not only accelerate returns handling but also reduce order picking errors, which in turn reduces the baseline return rate. In automation hardware distribution, similar systems can bring returned parts directly to specialized test stations, making it easier to perform consistent diagnostics and quickly decide between repair, resale, or scrap.

Automation does not belong only in warehouses. Returns management platforms in ecommerce such as Loop, ReturnLogic, and ReverseLogix demonstrate what software can do: automatic label generation, self-service portals, integrated fraud checks, and analytics dashboards. For industrial distributors and OEMs, the right returns module in an ERP or a dedicated returns management system can perform the same functions. The specifics vary, but the goals are the same: reduce manual handling, shorten turnaround time, and turn return reasons into engineering feedback.

Managing Risk: Fraud, Safety, and Compliance

Fraud in industrial returns does not always look like retail fraud, but it can be just as damaging. The retail statistics are sobering. As noted earlier, one survey found that 13.7 percent of returns were fraudulent, and other research put the figure around 6.5 percent. Common techniques include returning stolen goods, using false receipts, or deliberately abusing lenient policies.

In automation, risk often centers on misrepresentation and swapped components. Examples include returning boards that have been scavenged for parts, claiming “dead on arrival” on devices wired incorrectly, or returning counterfeit items purchased elsewhere. To manage this, leading returns automation guides recommend requiring serial numbers, using photos or video evidence before authorizing certain returns, and keeping a history of customer return behavior.

Safety and compliance add another layer. A safety relay that has seen a hard trip in a machine guarding system is not just a commodity part. Returning it without proper labeling, decontamination, and documentation can put both the supplier and future users at risk. For equipment used in hazardous locations or in contact with process media, your policy should spell out decontamination requirements and prohibit returns where contamination cannot be safely managed.

Consumer protection law is more prominent in ecommerce, but industrial buyers are not exempt from regulation. Different jurisdictions have different rules about warranties, merchantability, and what must be disclosed in a policy. While the details vary by country and state, the principle is consistent across the research: vague, shifting, or misleading policies invite disputes and legal exposure. Clear, stable language backed by internal training is not just good customer service; it is risk management.

Practical Advice by Role

The same return policy looks very different depending on where you sit in the value chain. A few patterns show up repeatedly across projects.

For System Integrators

If you are a system integrator, you live in the middle. You are responsible to your end customer but dependent on distributors and manufacturers. My strongest advice is to treat return policy reviews as part of your project risk assessment rather than an afterthought. During proposal and purchasing phases, identify which items are custom or non-returnable and highlight that to your customer. For critical or expensive components, discuss return and warranty expectations explicitly before you place orders, especially if you are expected to stock spares.

Document everything. Capture serial numbers at installation, keep photos of panel builds, and log any abnormal failures. When you need to initiate an RMA, a well-documented case accompanied by clear photos and test data gets resolved far faster than a vague complaint.

For OEMs and Machine Builders

If you build machines or skids, you are often both supplier and customer. You buy components from vendors and then issue your own warranty to end users. The research on customer behavior around returns applies to you as much as to any retailer. Buyers check policies, and a bad returns experience will push them elsewhere.

Design your own return policy with your upstream suppliers in mind. If your vendors offer thirty day return windows and one year warranties, and you promise your customers ninety day returns and two year warranties, you have just taken on risk that may or may not be priced into your machines. Align your commitments with your supply base where you can, and where you choose to be more generous, make sure you understand the cost and have processes to control abuse.

For End Users and MRO Teams

If you run plants, you are usually on the receiving end of these policies, but you are not powerless. Use your purchasing leverage to negotiate sensible terms on high-volume parts and critical spares. Ask for clarity on how warranty claims are handled, including testing methods and typical turnaround times. When a device fails, follow the procedure: tag the part, record symptoms and process conditions, and send it back promptly.

At the same time, look at your own data. If a particular line has an unusually high rate of “failed” drives that the manufacturer tests as healthy, you may have power quality or application issues. If you consistently return the wrong variant of a sensor, review your internal part-numbering and specification practices. Many of the problems that show up as returns actually start in design, documentation, or maintenance.

Short FAQ

Why are industrial suppliers so strict about unopened packaging and “unused” condition?

Suppliers need to be able to guarantee that a returned part can safely go back into stock and out to another customer. Once terminals have been wired, firmware flashed, or a device mounted in a panel, the supplier may not be able to verify that its life has not been shortened or that safety ratings are intact. Research on ecommerce returns emphasizes the need for resellable condition; in automation the stakes are higher because failures can cause safety incidents, not just dissatisfaction.

How much return flexibility should we build into project planning?

Use return windows and non-returnable categories as constraints when you plan procurement. If a vendor only accepts returns on unopened catalog items for thirty days from shipment, ordering all drives and panels six months before commissioning assumes you will not need to return them. In my experience, it is usually better to phase orders for configurable, high-value parts closer to when you will install and test them, even if that means a little more coordination effort.

What should we include when we ship automation parts back under RMA?

At minimum, include the RMA number on the label and paperwork, the original order or invoice reference, the serial number, and a concise description of the issue. Photos printed or attached digitally are valuable, especially for physical damage. The more structured your information, the easier it is for the supplier to reproduce problems and categorize the return. Case studies in automotive and retail both show that precise, standardized return data leads to faster resolutions and better quality improvements.

Closing Thoughts

Return policies for automation parts are not just legal boilerplate. They are a practical tool for managing risk, protecting uptime, and turning failures into feedback. If you treat them with the same discipline you bring to safety circuits and control logic, you will spend less time arguing about RMAs and more time keeping machines running. As a long-term project partner, my advice is simple: learn the rules, negotiate where it matters, and build your own processes so returns work for you instead of against you.

References

- https://www.autostoresystem.com/insights/enhancing-returns-management-in-retail

- https://cart.com/case-studies/thursday-boot-company

- https://www.chargeflow.io/blog/why-e-commerce-return-policy-and-how-write-one

- https://www.clickpost.ai/blog/ecommerce-return-policy

- https://eliteextra.com/what-you-need-to-know-about-effective-returns-management/

- https://www.gorgias.com/blog/ecommerce-returns-best-practices

- https://www.intellinetsystem.com/casestudies/streamlining-spare-parts-returns

- https://www.jackcooper.com/returns-management-a-simple-guide-for-every-business/

- https://www.returnalyze.com/blog/the-power-of-policy-how-return-policy-shapes-returns-and-sales

- https://returngo.ai/complete-guide-to-returns-automation/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment